Basic properties of superconductors

Perfect conductivity

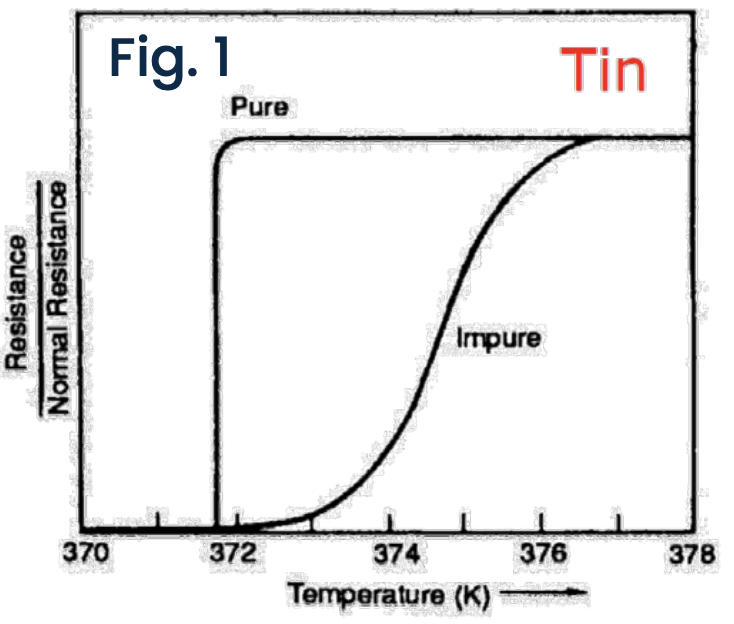

The electrical resistance of a superconductor undergoes a complete disappearance when the material is cooled below a critical temperature

Resistivity is never really equals to 0 but is

Perfect diamagnetism (Meissner effect)

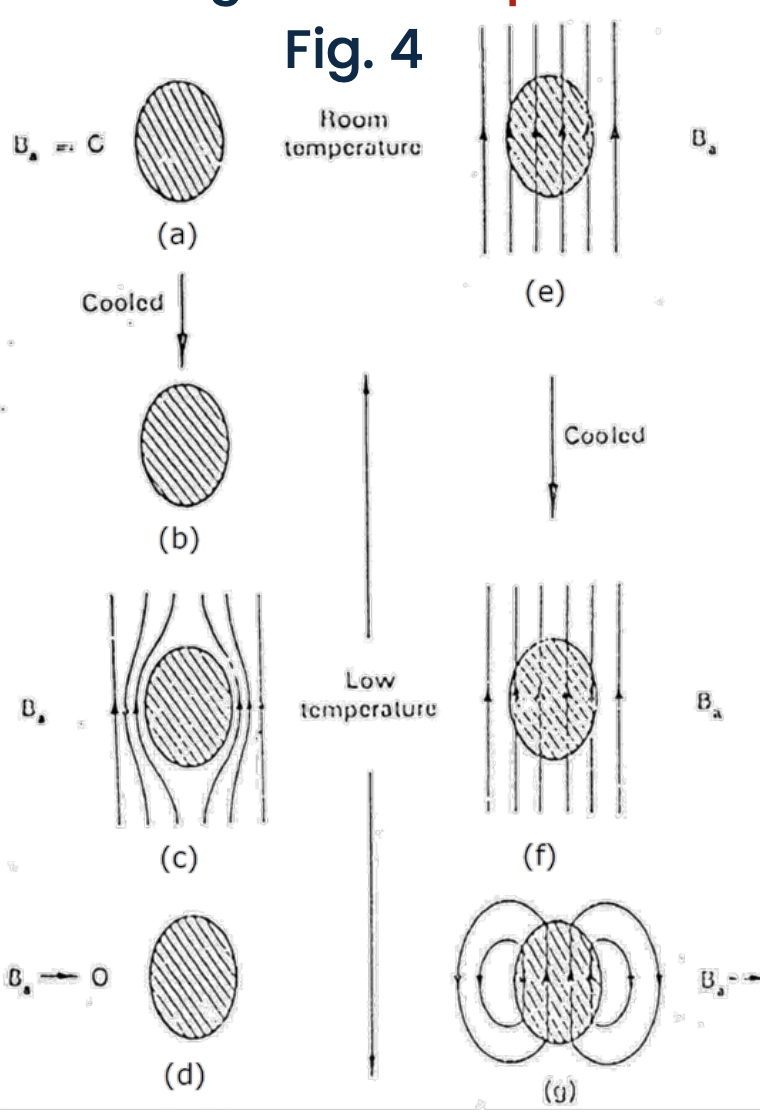

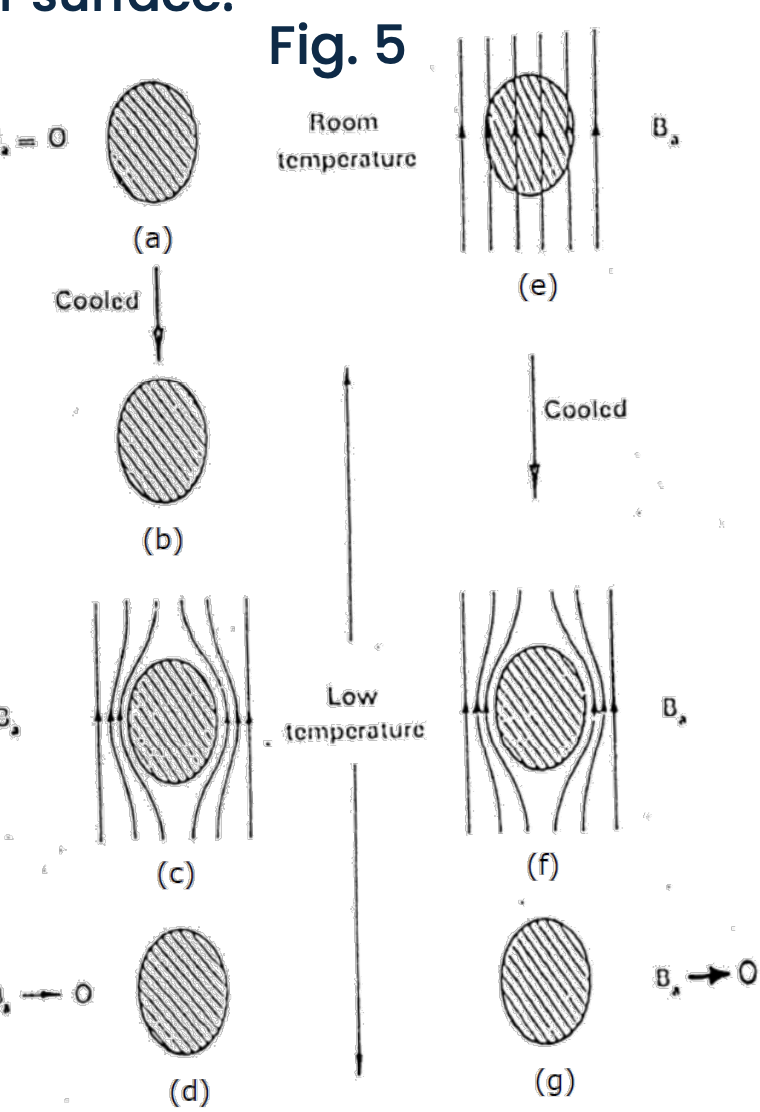

The Meissner effect shows that superconductivity is more than just perfect conductivity

Both superconductors and perfect conductors react to the application of an external magnetic field by screening it via dissipation-less eddy currents within a thin surface layer at their surface.

Note

Eddy Currents: The mechanism for this screening in both types of materials involves what are known as eddy currents. Eddy currents are loops of electric current induced within conductors by a changing magnetic field in the conductor, according to Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. These currents create their own magnetic field, which opposes the external field.

Dissipationless Currents: In both superconductors and perfect conductors, these eddy currents are dissipationless. In regular conductors, eddy currents lose energy over time due to the resistance in the material (this is why transformers heat up, for example). However, in perfect conductors and superconductors, these currents can flow without energy loss. In perfect conductors, this is a theoretical idealization; in superconductors, this is due to the material’s unique quantum mechanical properties.

Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force.

There are however differences between the two type of conductors:

Perfect conductors only conserve the magnetic flux inside them. Their magnetic state depends on their cooling history. A perfect conductor will expel a magnetic field only if it is applied after it has been cooled below

Superconductors always expel the magnetic flux as long as the magnetic field is not large enough to destroy the superconducting state. A magnetic field will be expelled as the sample is cooled through

The diamagnetism is perfect only for bulk samples, since the magnetic field does penetrate a finite distance

Critical magnetic field(s) and critical current density

The Meissner effect further implies that superconductivity is destroyed by a critical magnetic field

Normal State Energy: In the normal state, the electrons in a material behave as independent particles, scattering off impurities and lattice vibrations (phonons), which leads to electrical resistance.

Superconducting State Energy: In the superconducting state, electrons pair up into Cooper pairs. These pairs are bound together by lattice vibrations and move through the lattice without scattering, leading to zero electrical resistance. The formation of Cooper pairs lowers the overall energy of the electron system.

Energy Difference: The condensation energy is essentially the difference in the free energy of the material between these two states (normal state and superconducting state) at absolute zero temperature. This energy difference is crucial because it determines the stability of the superconducting state and influences various properties of superconductors, including critical magnetic fields and critical currents

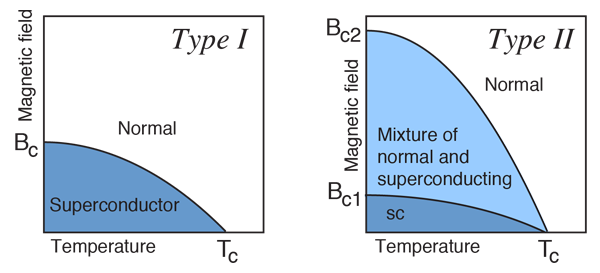

In type I superconductors (usually pure simple elements) the transition from the Meissner to the normal state is abrupt, we get out of the state of superconductivity give that we raise the temperature too high or apply too strong a magnetic field.

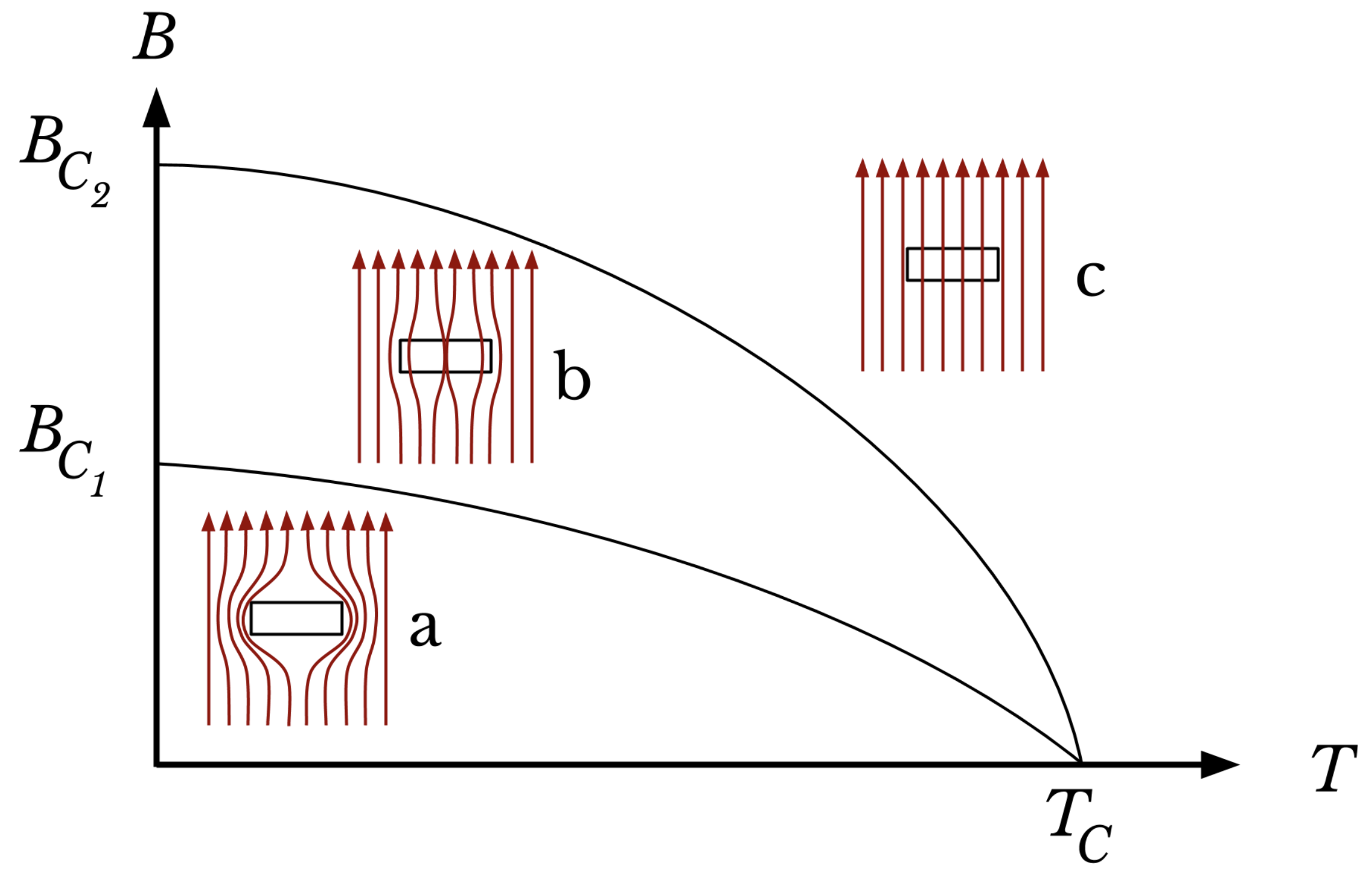

In type II superconductors (usually alloys or multi-atomic compounds) two distinct critical magnetic fields exist which separate the Meissner state from the normal state via an intermediate mixed state where a partial penetration of the magnetic field occurs in the so-called vortex lattice, is called in this manner because in this scenario some magnetic filed vortices are created where the magnetic flux is not 0.

Since exists a field that is able to destroy the superconducting state (

Energy gap

Should not be confused with the energy gap of semiconductors

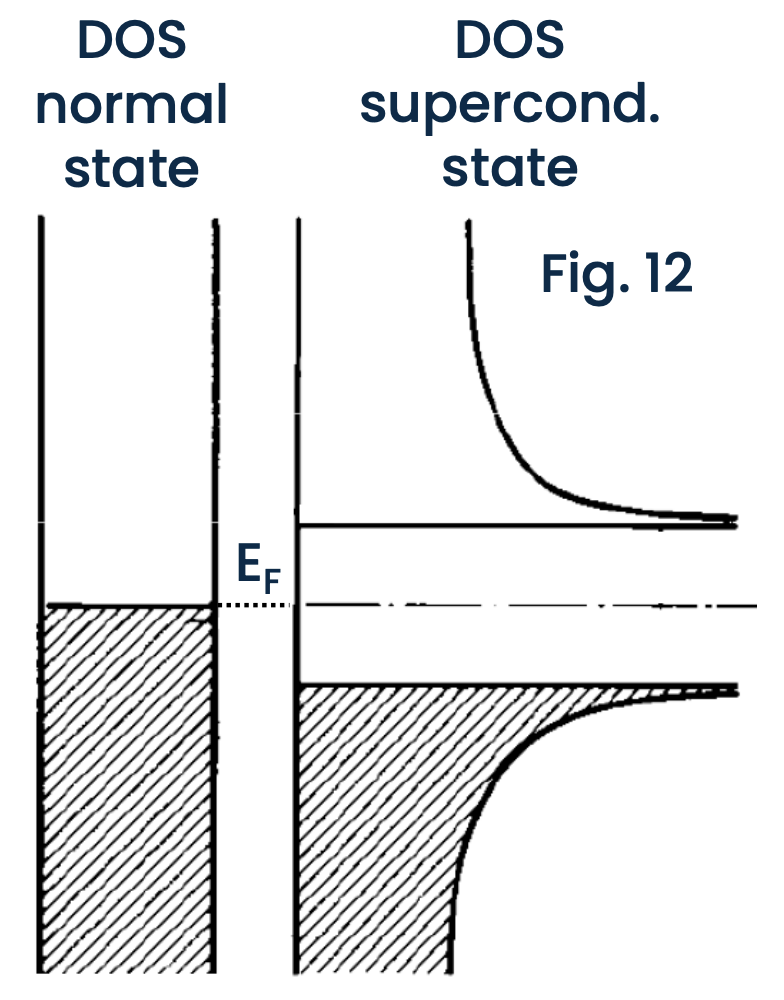

The band gap in superconductors refers to an energy gap that safeguards the stable, condensed state of Cooper pairs in the superconducting phase, preventing the transition back to the normal state. This energy gap acts as a protective barrier for the Cooper pairs. It requires a certain amount of energy to break these pairs apart and push the electrons into higher energy states. As long as the energy available (such as thermal energy) is less than this gap, the Cooper pairs remain intact, and the material stays in its superconducting state.

“Super” charge carriers (and supercurrents) exist only for excitation energies below the energy gap; above them they break into standard electronic quasiparticles.

Note

the DOS shown are the desity of state of electronic quasiparticles, not of the cooper pairs. Indeed the cooper pairs are all condensed at the chemical potential.

Macroscopic Quantum Model (MQM)

Superconductivity is an inherently quantum mechanical phenomenon that manifests itself over macroscopic scales.

There exists a macroscopic quantum wavefunction

This approach doesn’t delve into the detailed microscopic origins of superconductivity, much like the classical model. However, it emphasizes the crucial aspect that superconductivity is a phenomenon of coherence among all superelectrons. This concept is similar to the quantum understanding of electromagnetism. In electromagnetism, while individual photons are considered quantum particles of light, a large group of photons exhibiting coherent behavior (like in a laser) can be effectively represented by a single electromagnetic field.

London equations

Starting form the Schrödinger equation for a charged particle in electric and magnetic fields we can get :

that is the most general form for the supercurrent in an isotropic superconductor, since it includes the possibility that the local supercarrier density is variable in both space and time. In many practical situations and devices, however, it is appropriate to consider a constant and approximately uniform density of supercarriers, in this case:

Taking the curl of this form of the supercurrent equation we get the 2nd London Equation that describes perfect diamagnetism (Meissner effect) and describe the response of a superconductor to a magnetic field:

combining this Eq. with the 4th Maxwell equation in the first case and taking the curl of the 2nd London Equation in the second we get:

Thus any magnetic field is exponentially screened by an induced supercurrent, and both are confined to a surface layer of thickness

from the Schrödinger we can also derive:

that is the 1st London equation, that describe the response of a superconductor to an electric field. We can notice not only the exponential increase in supercurrent under the application of an electrostatic field due to the absence of dissipation, but also an additional term proportional to the gradient of kinetic energy of the superelectrons.

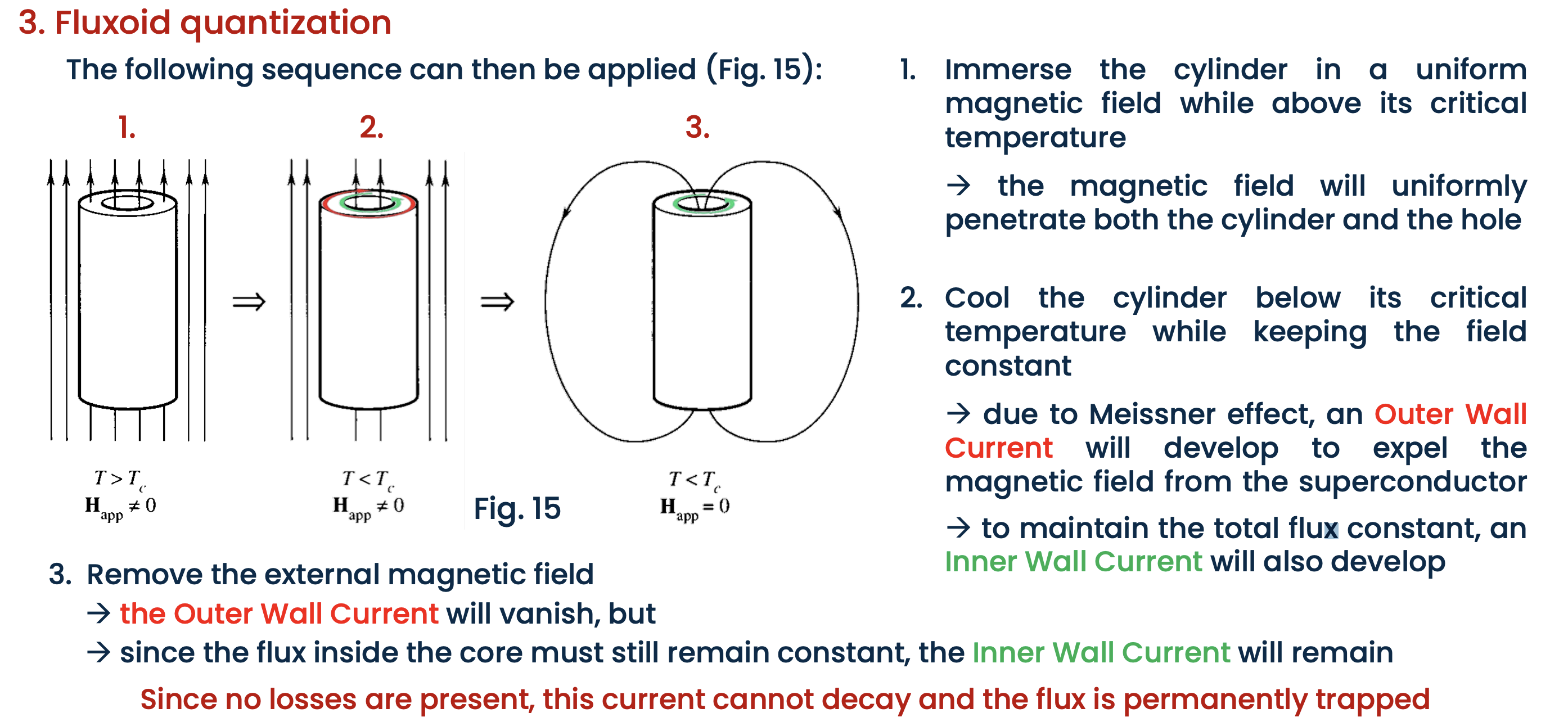

Fluxoid quantization

Fluxoid quantization is the most basic property of a superconductor that cannot be described in terms of classical models and requires a full quantum mechanical treatment

The integral of the supercurrent times a constant

Let’s derive it: Consider the supercurrent of a homogeneous isotropic superconductor:

Integrating the Eq. over a contour C that enclosed a surface S we get

applying Stokes’s theorem:

thus we can write:

now recalling that the line integral of the gradient of any scalar function is the difference between the same function evaluated in the start and end-points we get:

Now, the phase of the wavefunction in a superconductor must be coherent, meaning it is uniform throughout the material. However, the phase itself is not a directly measurable quantity and can change by multiples of

thus we call the integral of the current and the magnetic field across a closed loop inside the superconductor, the “fluxoid” and this is linked with the phase difference by:

where

this relation holds for any shape of the closed contour C:

Simply-Connected Region: This is a continuous area without any holes. if you have a loop

Multiply-Connected Region: This is an area with at least one hole in it (like a doughnut). In this case, if you have a loop

Experiments

Fluxoid quantization can be directly probed by flux trapping experiments.