Transport Matrix

Davies, 5

A generalized “barrier” is any disturbance of an otherwise flat potential. We will start considering the step potential problem.

When an incoming electron approaches the potential barrier at position

The wave functions for the two region are:

with:

The wavevector

The continuity of the wavefunctions and of their first derivatives in

so making the calculation we get that:

these are our two boundary conditions. We can write the amplitudes

Since we can express

The

In general,

solving the system we get:

the relation above always apply in the case of

If instead of a barrier in

or

This approach can also be extended to subsequent regions and barriers. The power of the matrix formalism lies in the fact that the treatment becomes a straightforward multiplication of matrices.

also in the case of

If our system is invariant with respect to time inversion and is symmetric with respect to the barriers, the transfer matrix’s determinant is equal to 1 so, in these cases

and we have that

We can write the total transmission probability as:

Quantum and classical transmittance

we can see that the quantum case differ from the classical one not only when

Some of the parameters that influence the transmittance index:

Height of the Barrier: The probability of tunneling decreases exponentially with the increase in the barrier’s height.

Width of the Barrier: The tunneling probability decreases exponentially as the width of the barrier increases.

Mass of the Particle: Heavier particles have a lower probability of tunneling compared to lighter ones.

Resonant-tunnelling diode

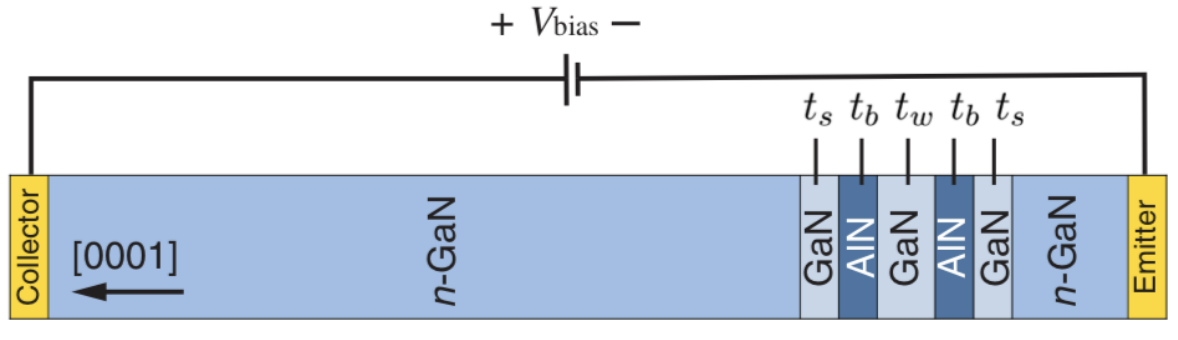

An interesting application of resonant tunneling is the RESONANT-TUNNELING DIODE which typically consists of a central layer of undoped GaAs separated from doped GaAs contact regions by means of

Resonant tunneling is induced by applying a variable voltage bias between the contacts which possibly matches the (first) resonant energy

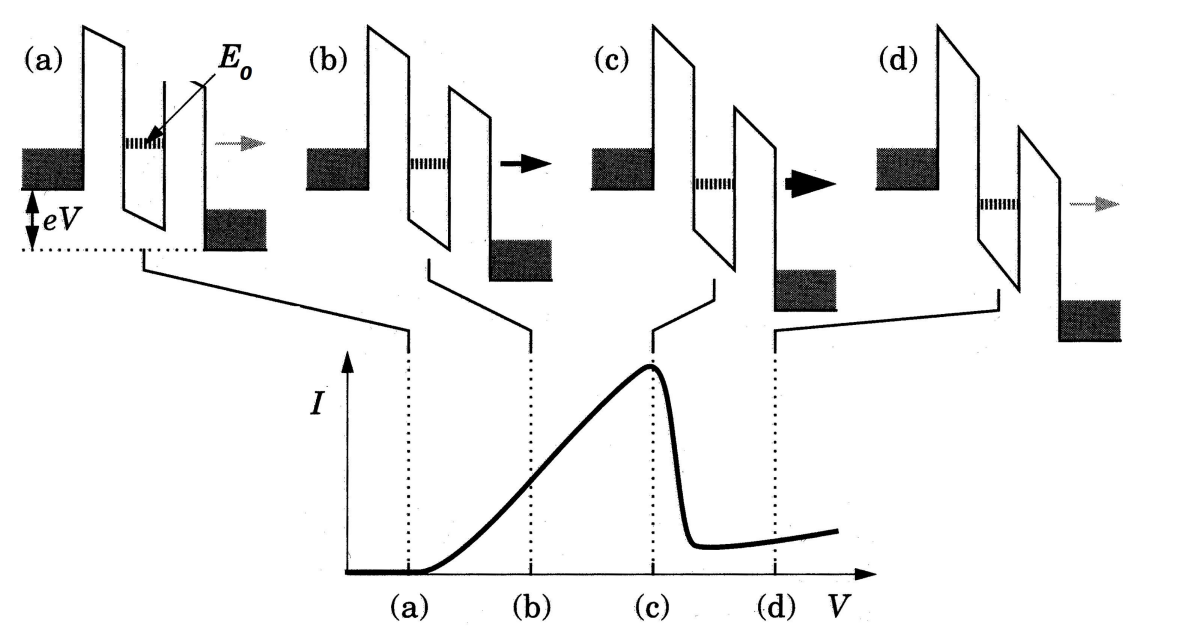

The image illustrates the operation of a resonant tunneling diode (RTD).

Section (a): Small Bias Applied

When a small voltage is applied across the device, the resonant level

Section (b): Increased Bias

As the voltage (bias) increases, the resonant level aligns with the Fermi level of the source, allowing electrons to tunnel through the well more easily. The alignment of the resonant level with the Fermi energy increases the current sharply because many more electrons have the right energy to tunnel through the resonant level.

Section (c): Higher Bias

When the bias is increased further, the resonant level moves below the Fermi level of the source. This condition still allows a significant number of electrons to tunnel through, so the current remains high, but there is a decrease in the current.

Section (d): Too High Bias

At a very high bias, the resonant level drops too low, below the energy of most electrons in the source. This misalignment means that fewer electrons have the energy to tunnel through the barrier, and thus the current decreases rapidly.

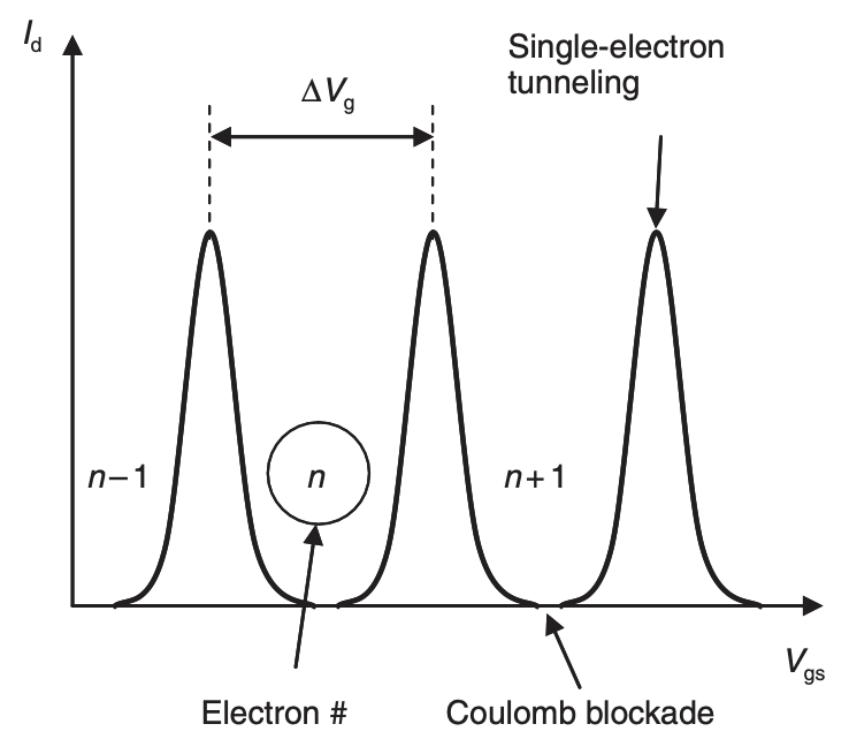

Coulomb blockade

Is a phenomenon where the transfer of an electron to a small conducting island is prevented due to the repulsive force (Coulomb force) from electrons already present on the island. In essence, it becomes energetically expensive for additional electrons to join the island once a certain number of electrons are present, due to the increase in electrostatic energy. This phenomenon applies a more restrictive condition for the transmission of electrons from source to drain towards the barriers. Indeed even if an electron has the right energy (energy in the range align with the resonant energy), it still might not get through because of the repulsion from other electrons.

The increase in electrostatic energy of the system associated with the transfer of a charge

When

where we replaced

we can notice that if

The Coulomb blockade prevents electrons from randomly moving onto the island due to thermal energy or electrical noise. It ensures that electron transfer only happens under very controlled conditions, the resonant condition.

This phenomenon can be exploit to create a transistor device which can control the flow of individual electrons. That is the principles used in SET (Single-Electron Transistor)