In a quantum dot we have

We have 3 dimension of confinement and zero degree of freedom for electrons.

We are able control the amount of charge in a quantum dot connecting the dot to electrodes.

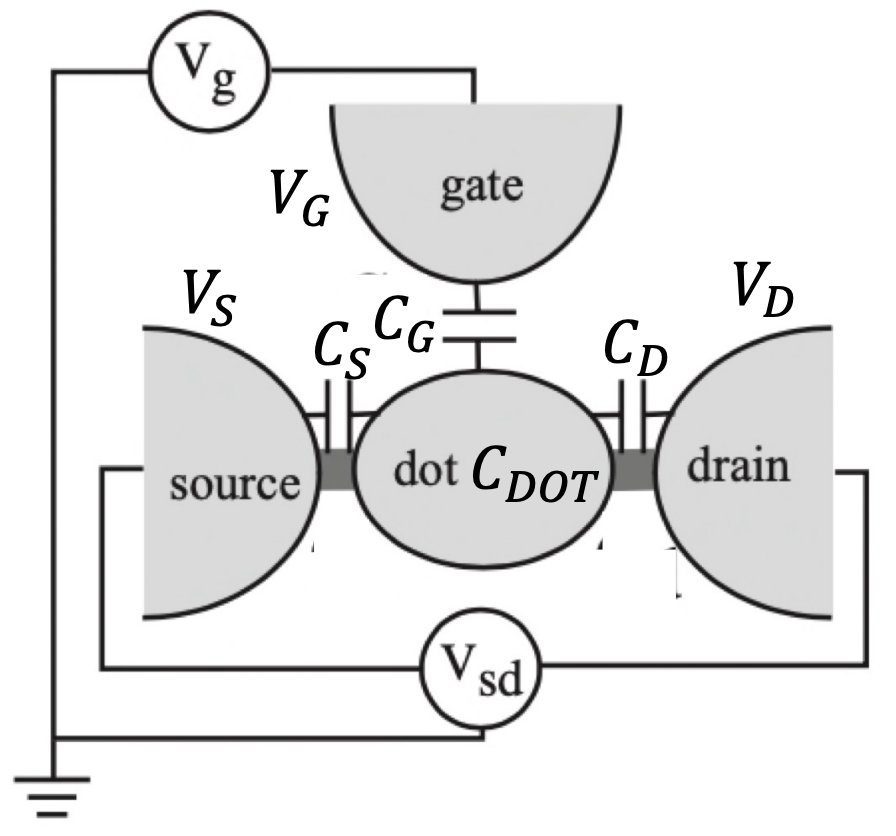

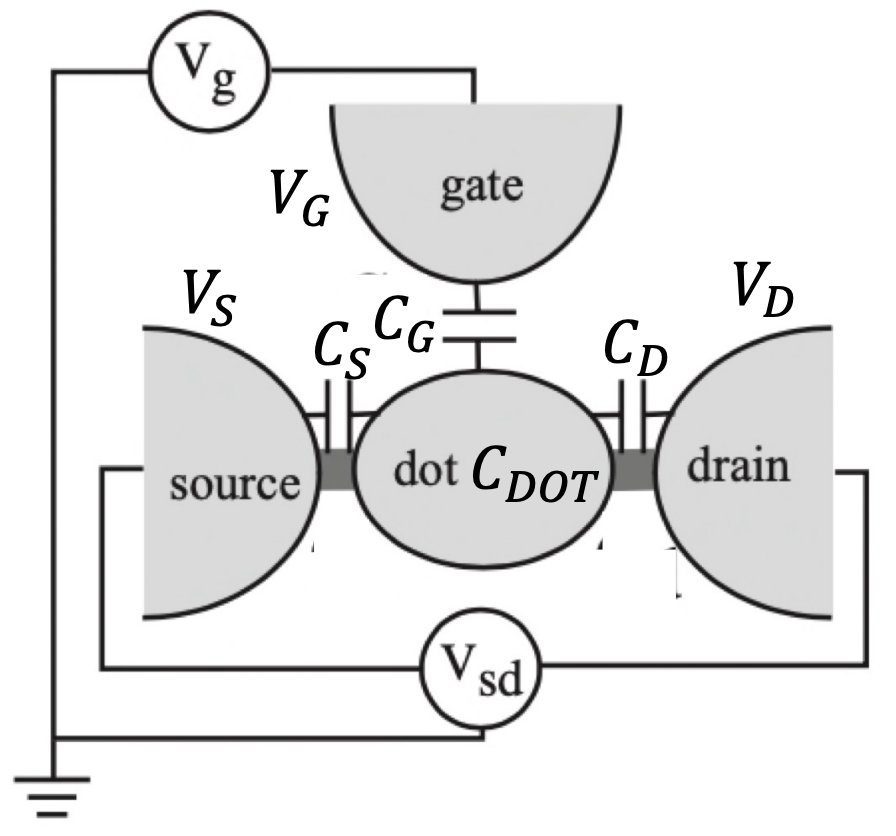

The dot can be coupled via tunnel barriers to reservoirs (source and drain), with which electrons can be exchanged. The dot is also coupled capacitively to a gate electrode, which can be used to tune the electrostatic potential of the dot with respect to the reservoirs.

Constant Interaction Model

In quantum dot systems, particularly when studying charge manipulation, the Constant Interaction Model is often employed as a simplifying approximation. This model helps to understand the electronic properties of quantum dots, especially when dealing with Coulomb blockade and single-electron tunneling phenomena. The Constant Interaction Model relies on two key approximations:

-

Constant Capacitance Assumption: This approximation assumes that the Coulomb interactions among electrons within the quantum dot, as well as between the electrons in the dot and those in the environment, can be parameterized by a single, constant capacitance value. This means that the charging energy of the quantum dot, which is the energy required to add an additional electron to the dot, is considered to be constant, regardless of the number of electrons already present in the dot. Under this approximation, the energy required to add each additional electron is the same, leading to equally spaced addition energy levels.

-

Independence of Single-Particle Energy Levels from Interactions: The second approximation is that the single-particle energy-level spectrum of the quantum dot is independent of the Coulomb interactions and, therefore, of the number of electrons. This approximation simplifies the theoretical treatment by treating the quantum dot as a simple potential well where the energy levels are determined by the dot’s size and shape, independent of its charge state.

Charge manipulation in quantum dots

We want to calculate the charge on the dot as function of the applied voltages on the electrodes. Recalling that

we start writing:

this formula leads us to:

We are, interested in the electrostatic energy variation induced by the addition of

Note

The electrostatic energy is summed up to the single electron energy in QD to find the total energy of the system:

The total energy of the quantum dot system with

the electrochemical potential

Substituting we get:

The electrochemical potential depends linearly on the gate voltage, The effect of

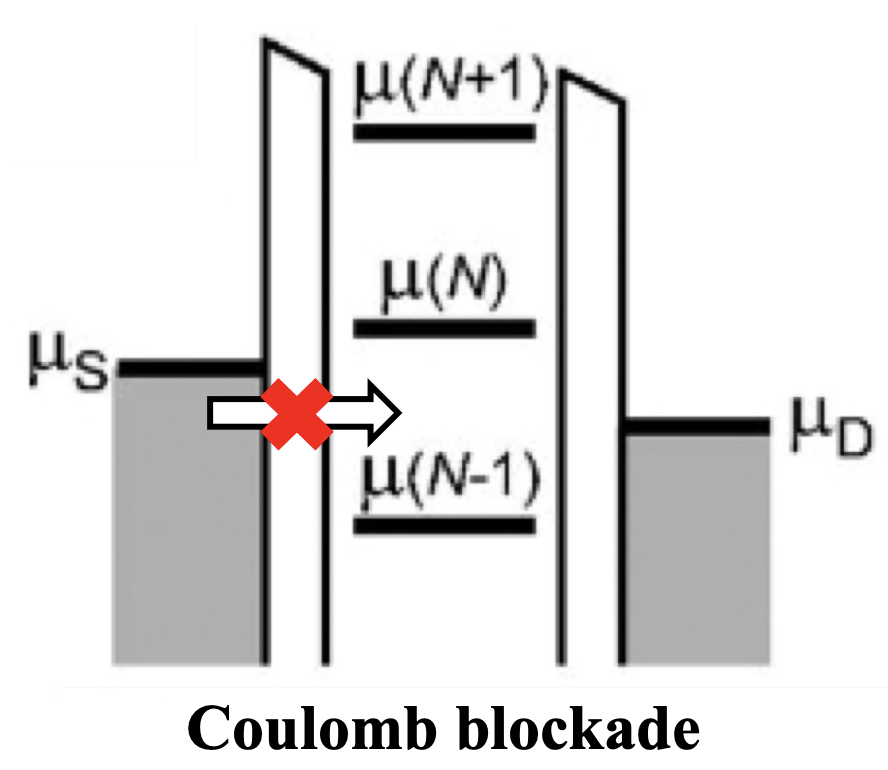

The electrochemical potential gives an indication of the energy requirements to add electrons to the dot. When the electrochemical potential does not match the energy provided by the gate voltage, electrons cannot tunnel through the quantum dot, effectively blocking the current - this is the Coulomb blockade. By adjusting the gate voltage, the energy levels within the dot can be tuned until they align with the source and drain, allowing electrons to tunnel through, and current to flow

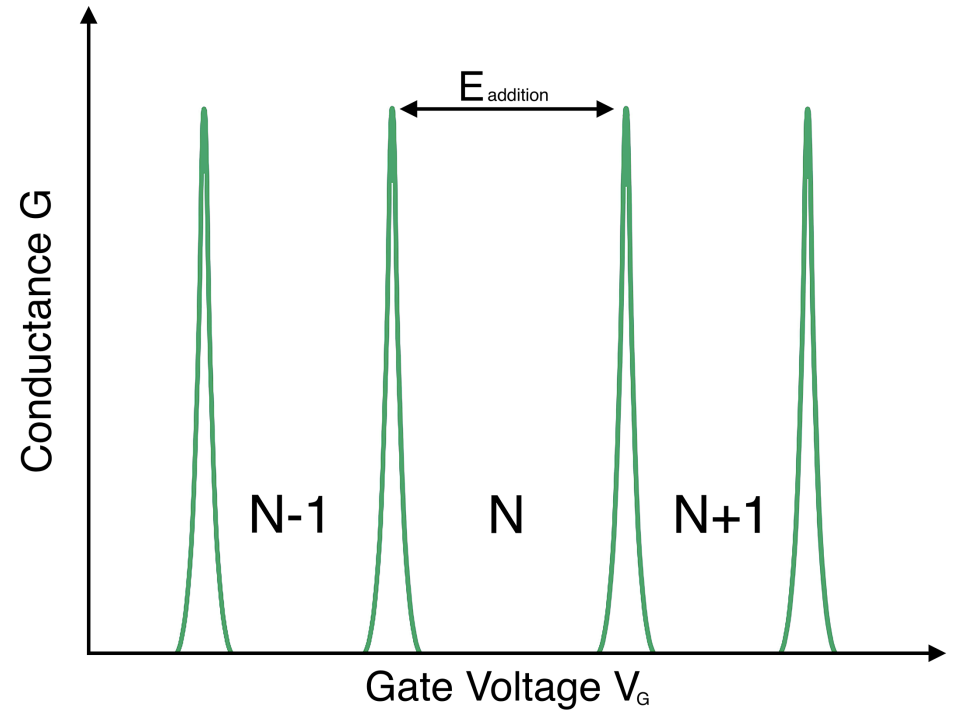

To unblock the dot, one must act on the applied voltages, either increasing the

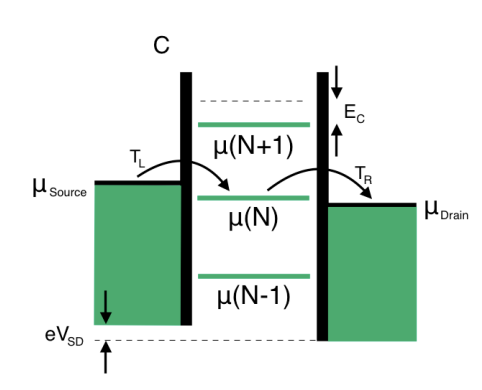

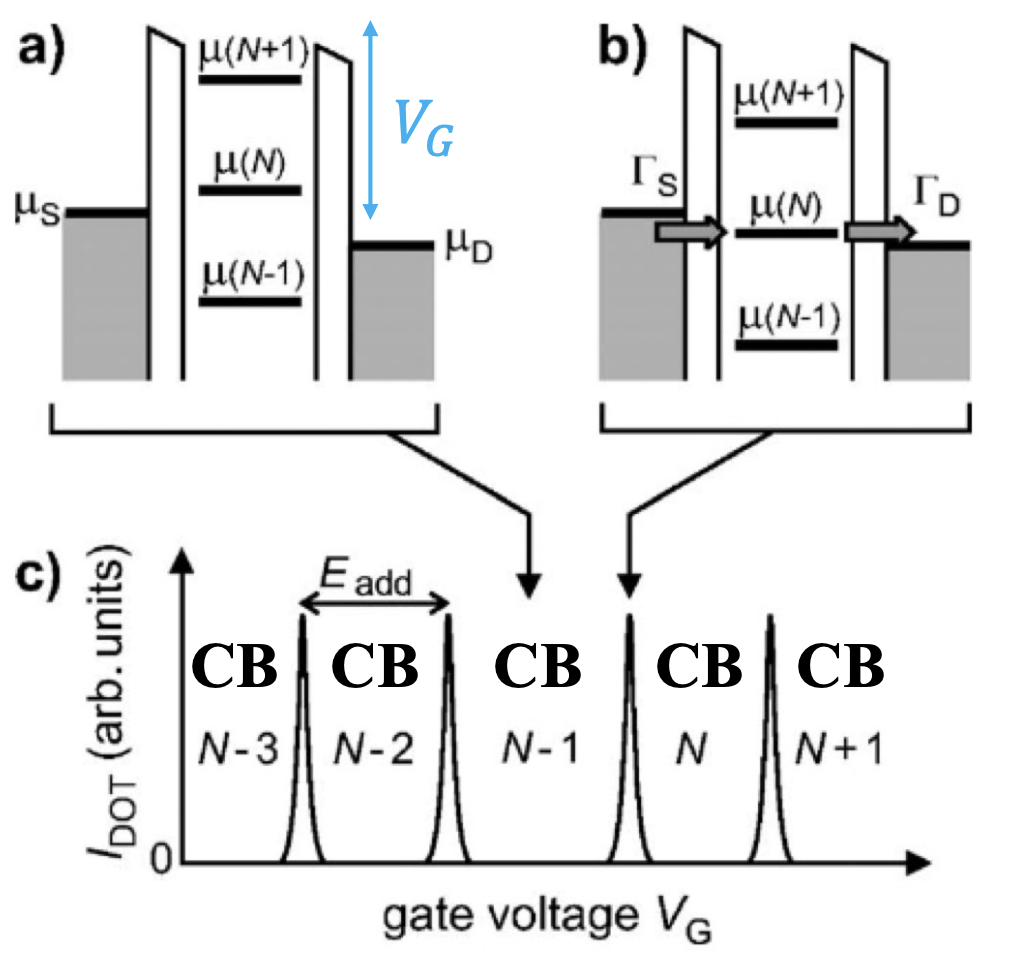

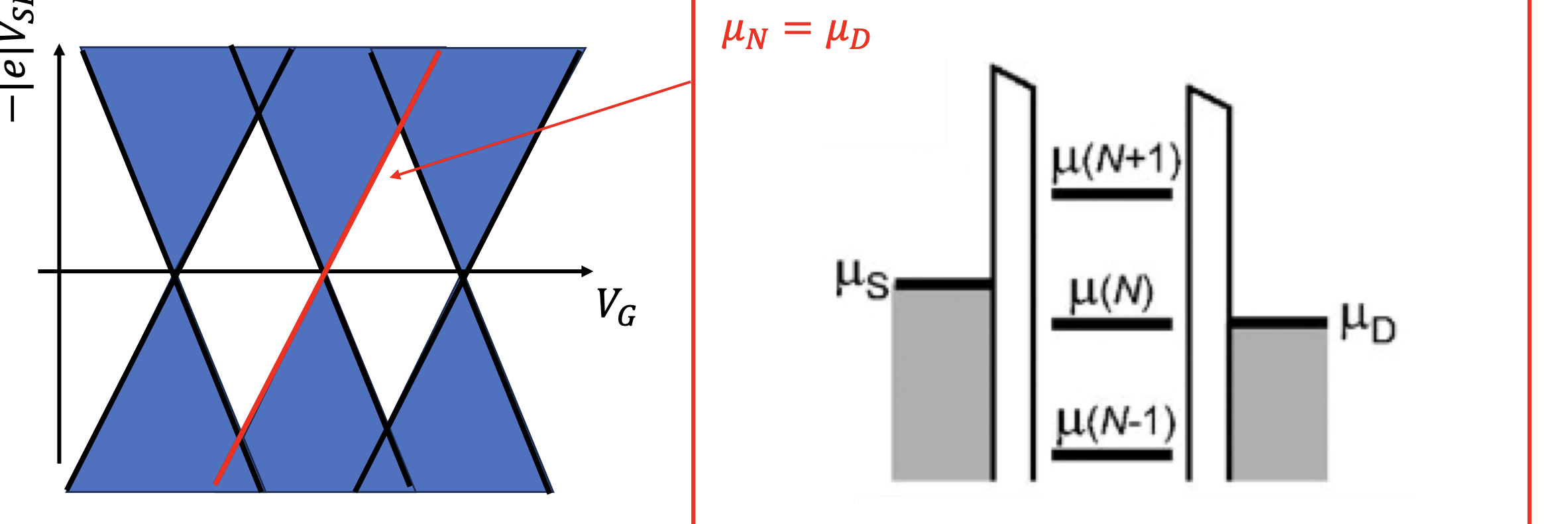

There are two main regimes of application of a

-

Low Bias

In the low bias regime, at most one level is within the bias window.

By definition, in the low-bias regime considered here, no excited states exist.

In the low bias regime, at most one level is within the bias window.

By definition, in the low-bias regime considered here, no excited states exist. -

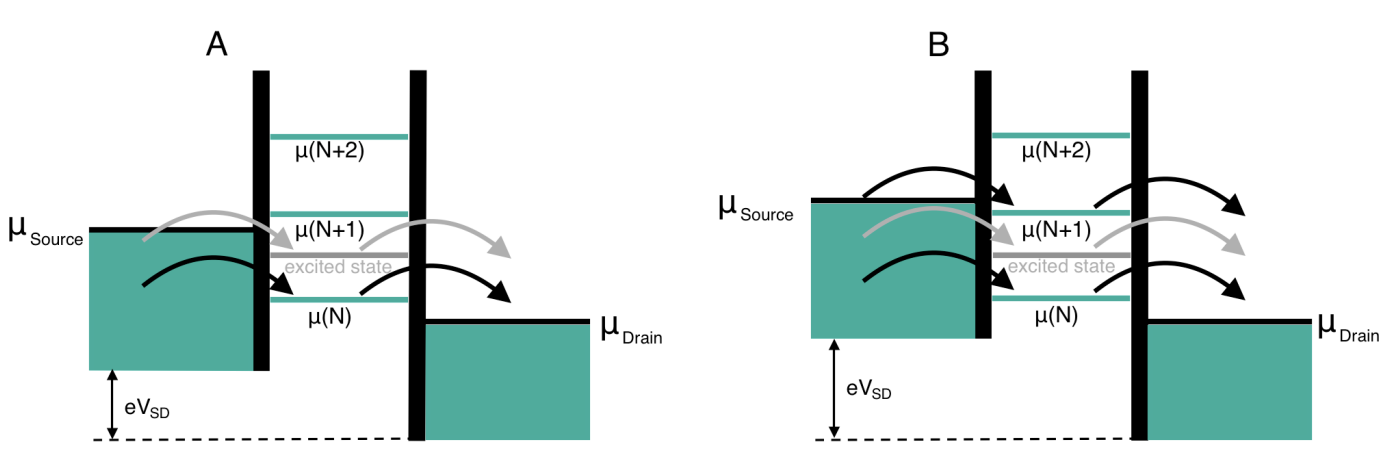

High bias

In the high bias regime, multiple levels can be within the bias window.

Electron transport is only possible when a level is in the bias window, i.e.,

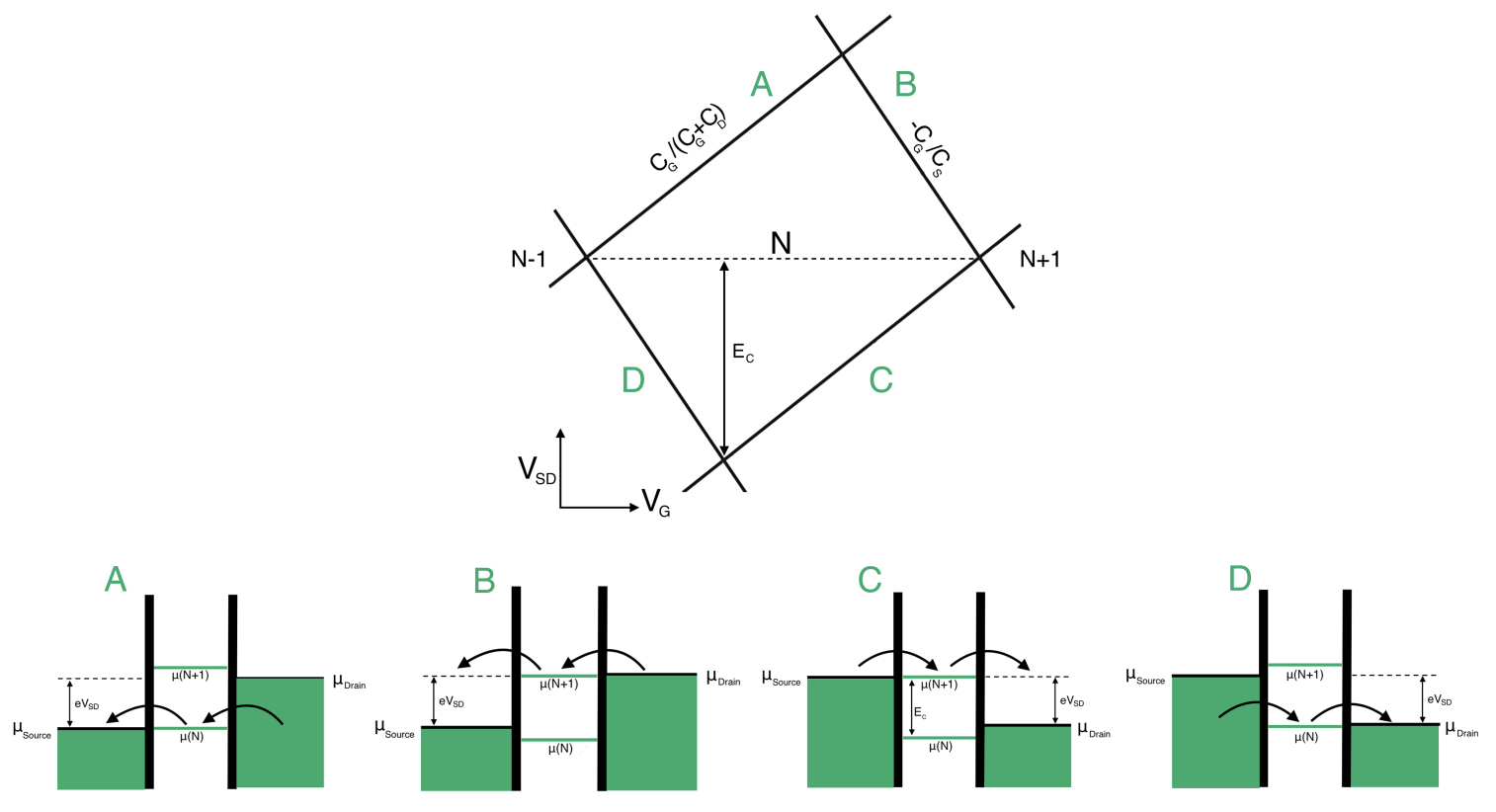

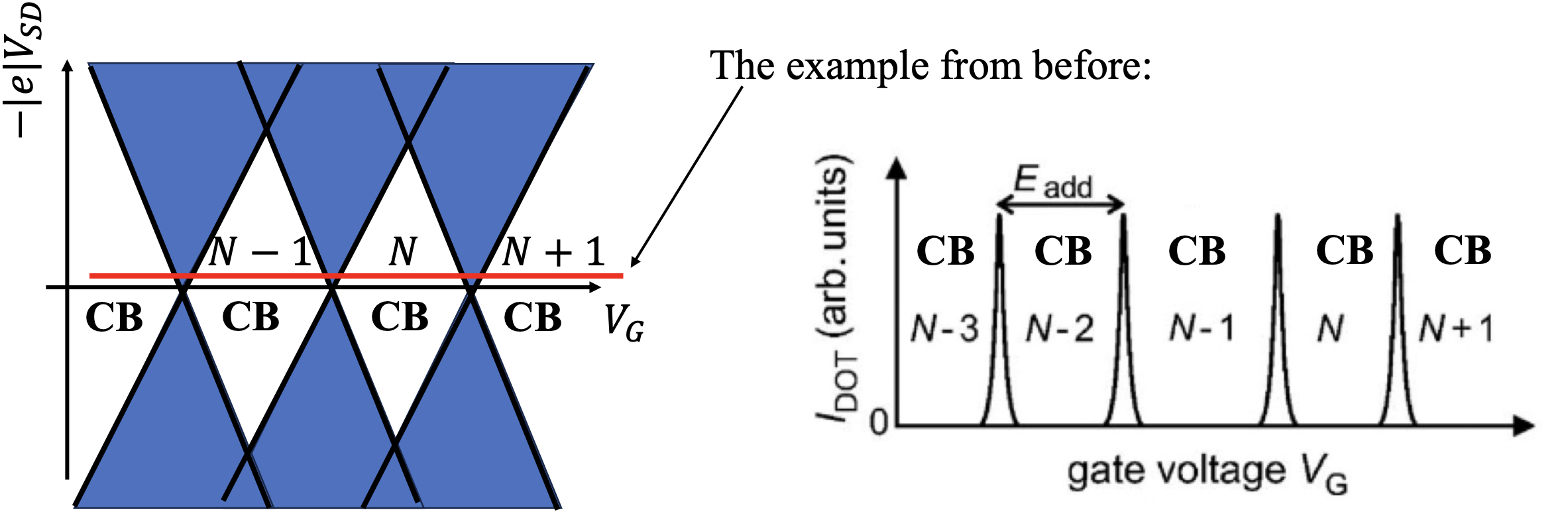

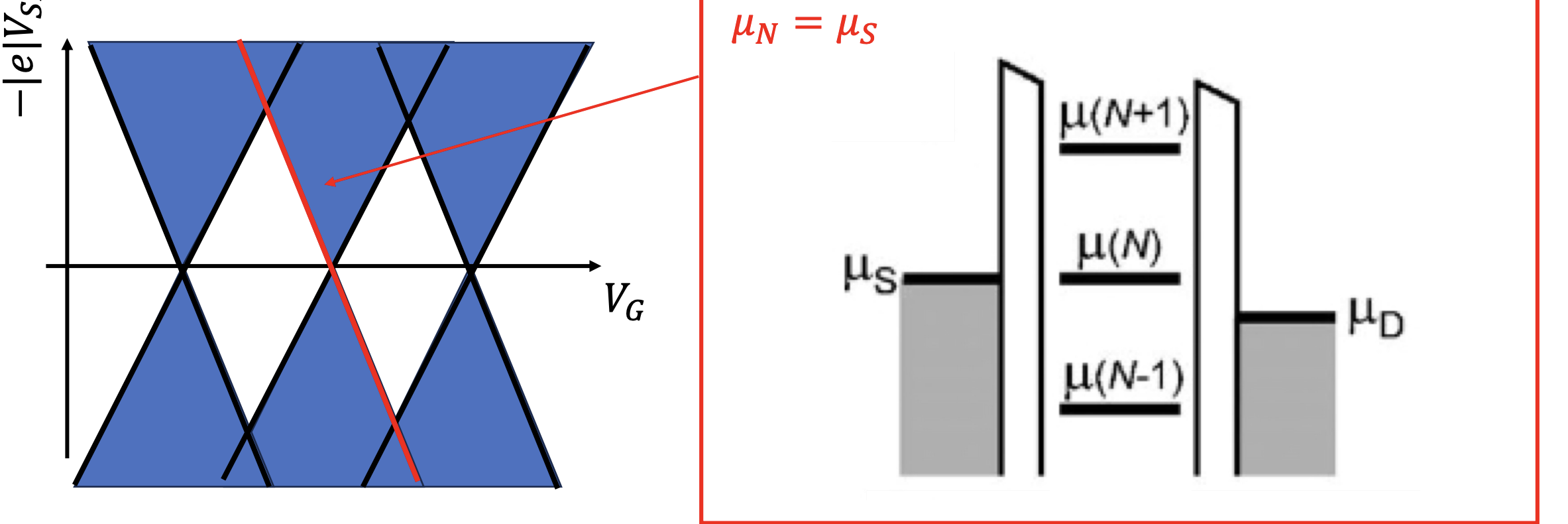

Coulomb blockade diamonds

Low Bias

A source-drain bias voltage versus gate voltage plot can be made. This plot is often called a level spectroscopy diagram or a stability diagram and always exhibits a characteristic rhombic structure. Inside the diamond-shaped regions, the number of electrons on the dot is fixed due to the Coulomb blockade effect and no current can flow through them. These regions are often called Coulomb diamonds. Each diamond corresponds to a fixed number of N electrons inside the dot. The points at the end of each diamond where the upper right and lower right edge of the diamond join along the gate voltage axis are called degeneracy points. At these points the energy of adding the

The shape of the Coulomb diamonds can be interpreted as follows:

If we assume that the bias is applied symmetrically so the voltage is applied in such a way that the source’s energy is increased by half the applied voltage

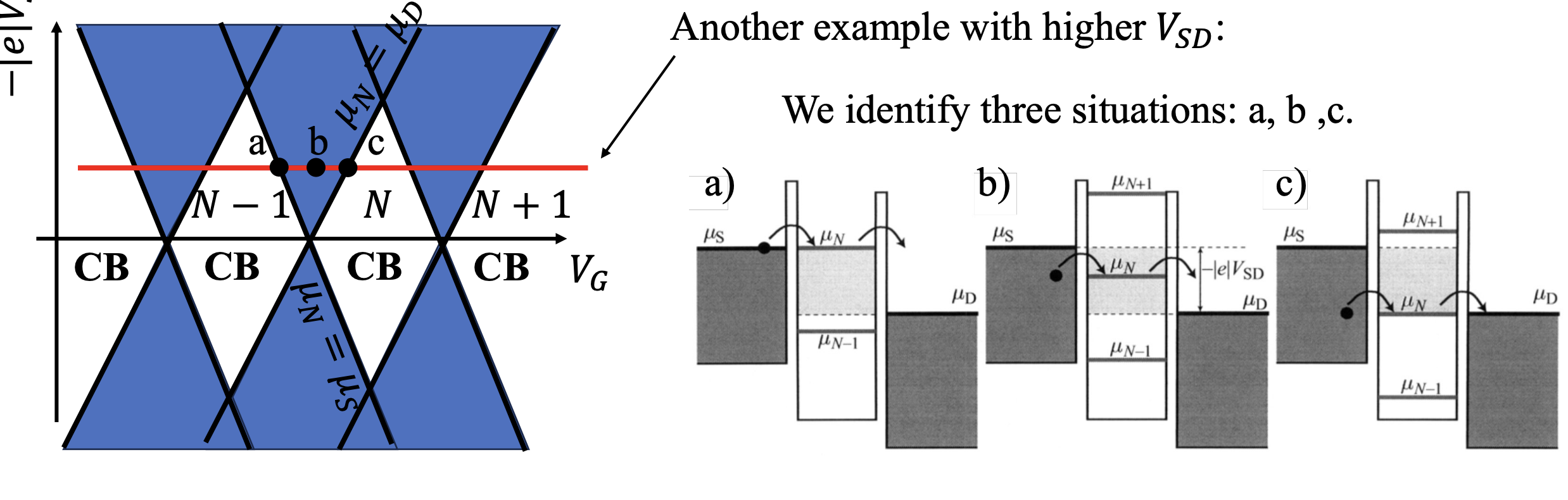

High Bias

At the high bias regime, multiple dot energy levels can participate in the charge tunneling. Every time an excited state level enters the (now widened) bias window together with an electrochemical potential level in the dot, an additional transport channel opens up allowing electrons to tunnel via one of the two levels. Also, multiple tunneling events can take place at the same time if multiple electrochemical potentials are aligned inside the bias window. The new transport channels due to the excited states appear in the stability diagram discussed earlier as lines running parallel to the diamond edges:

The plot describe transport with the same Coulomb blockade diamonds. This time accounting for the additional excited states.

Excited states (ES) can arise from a number of reasons. For example If a magnetic field is applied the spin up and down states are no longer degenerate but they split in energy due to Zeeman effect.

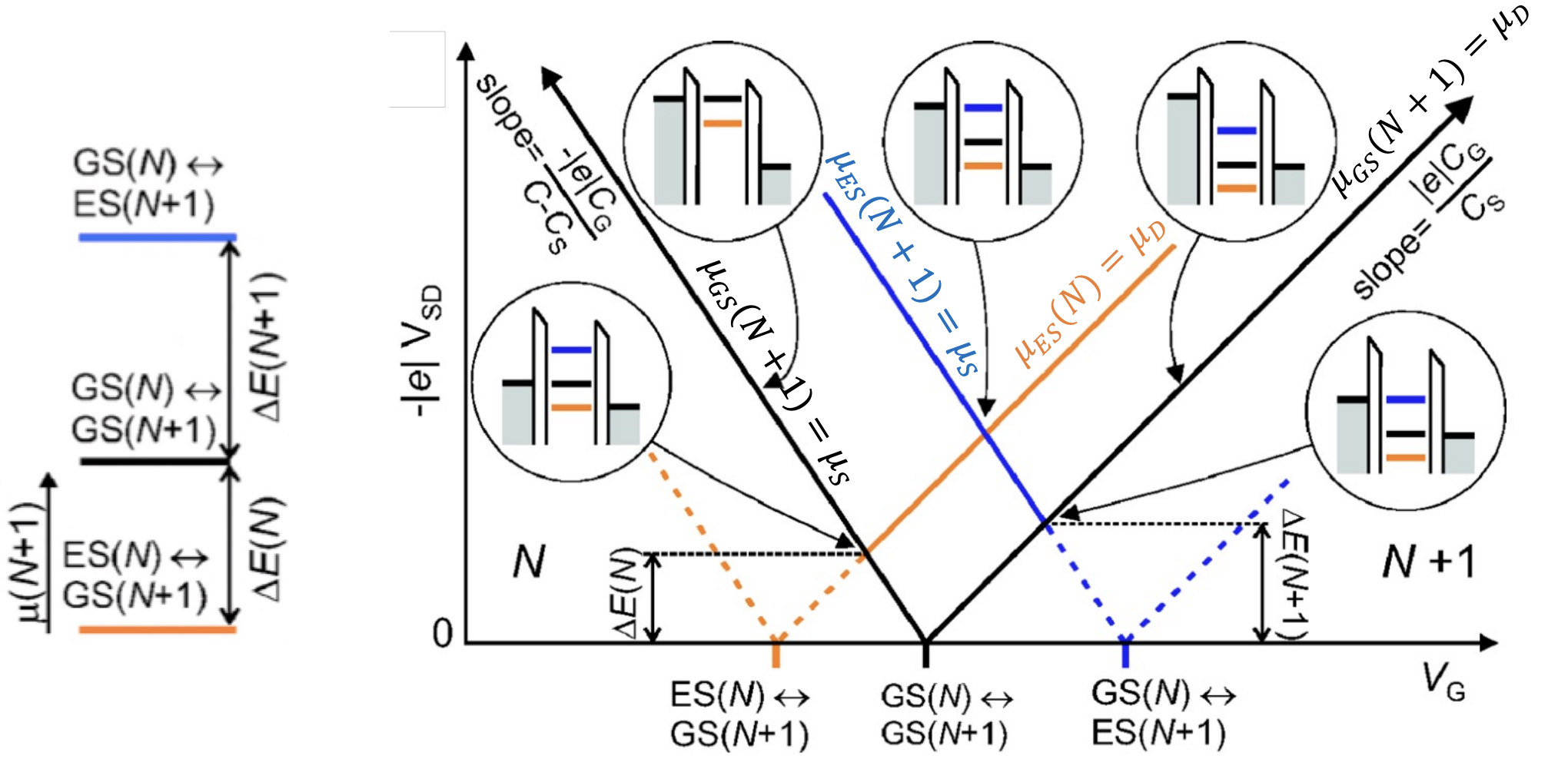

Interaction between QDots

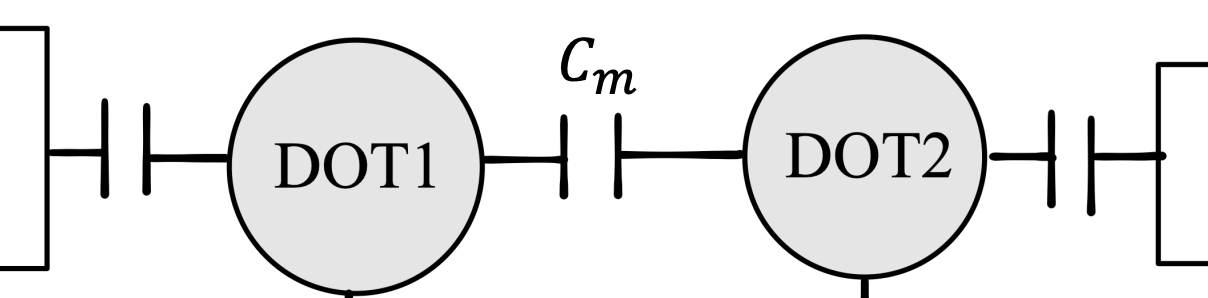

In a similar to a single quantum dot fashion, systems consisting of two coupled quantum dots can be fabricated. Where single quantum dots are regarded as artificial atoms, coupled double quantum dots can be considered as artificial molecules

Usually, two contributions to the coupling have to be considered:

- The electrostatic interaction between the electrons of neighboring dots (capacitive coupling)

- The possibility of electron tunneling between dots (tunneling coupling)

Capacitive coupling

The capacity coupling is modelled by a capacitance term

For large distances, the electrostatic interactions between dots are negligible so

In this case, the amount of charge on one node is not influenced by the other.

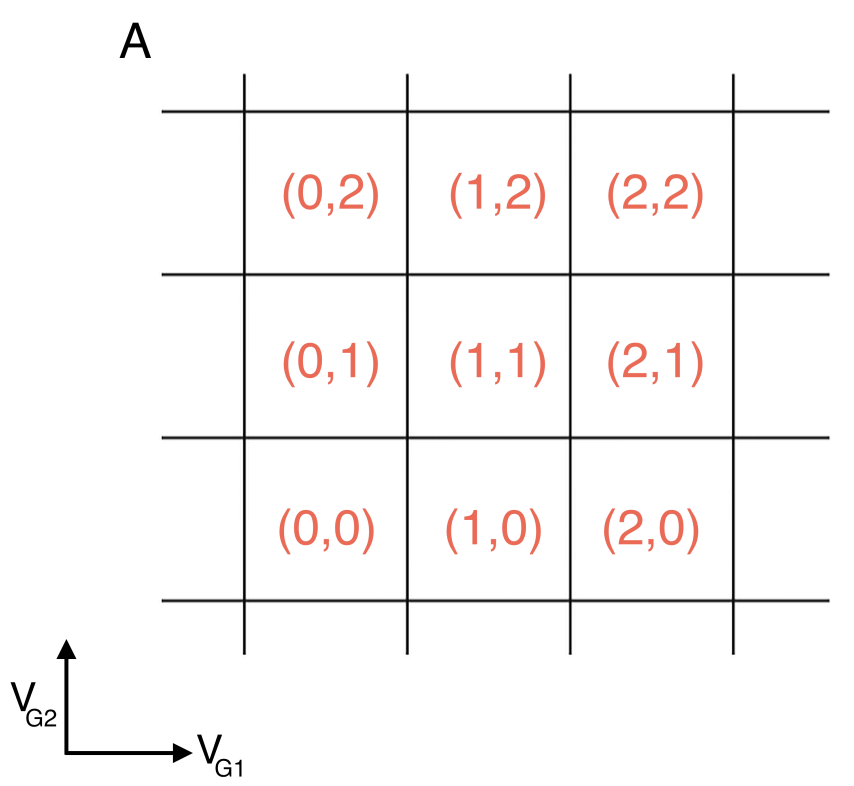

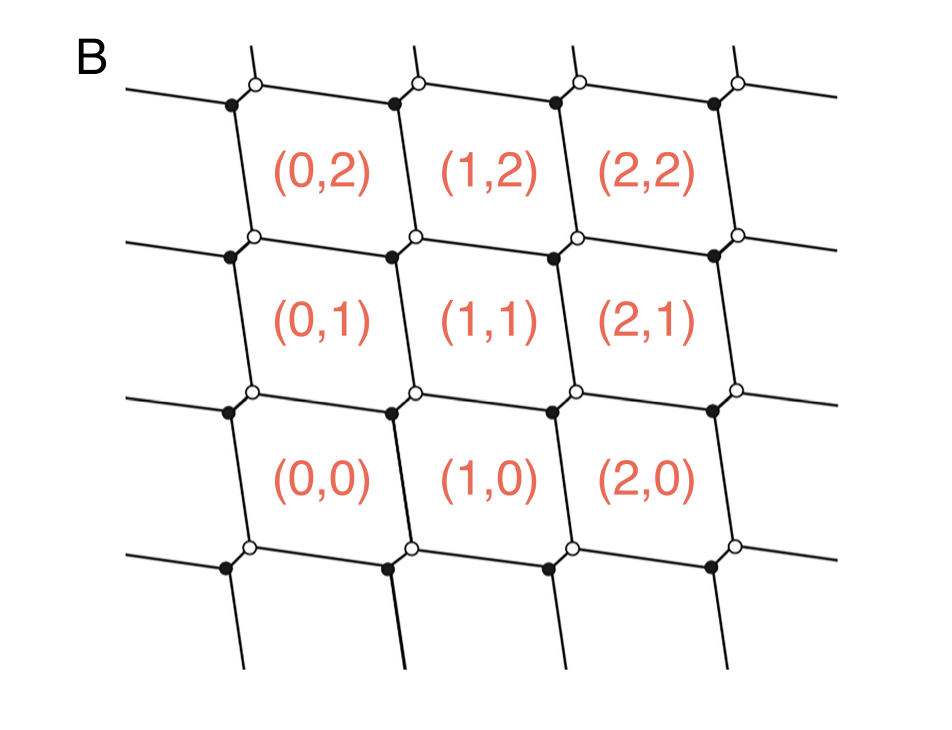

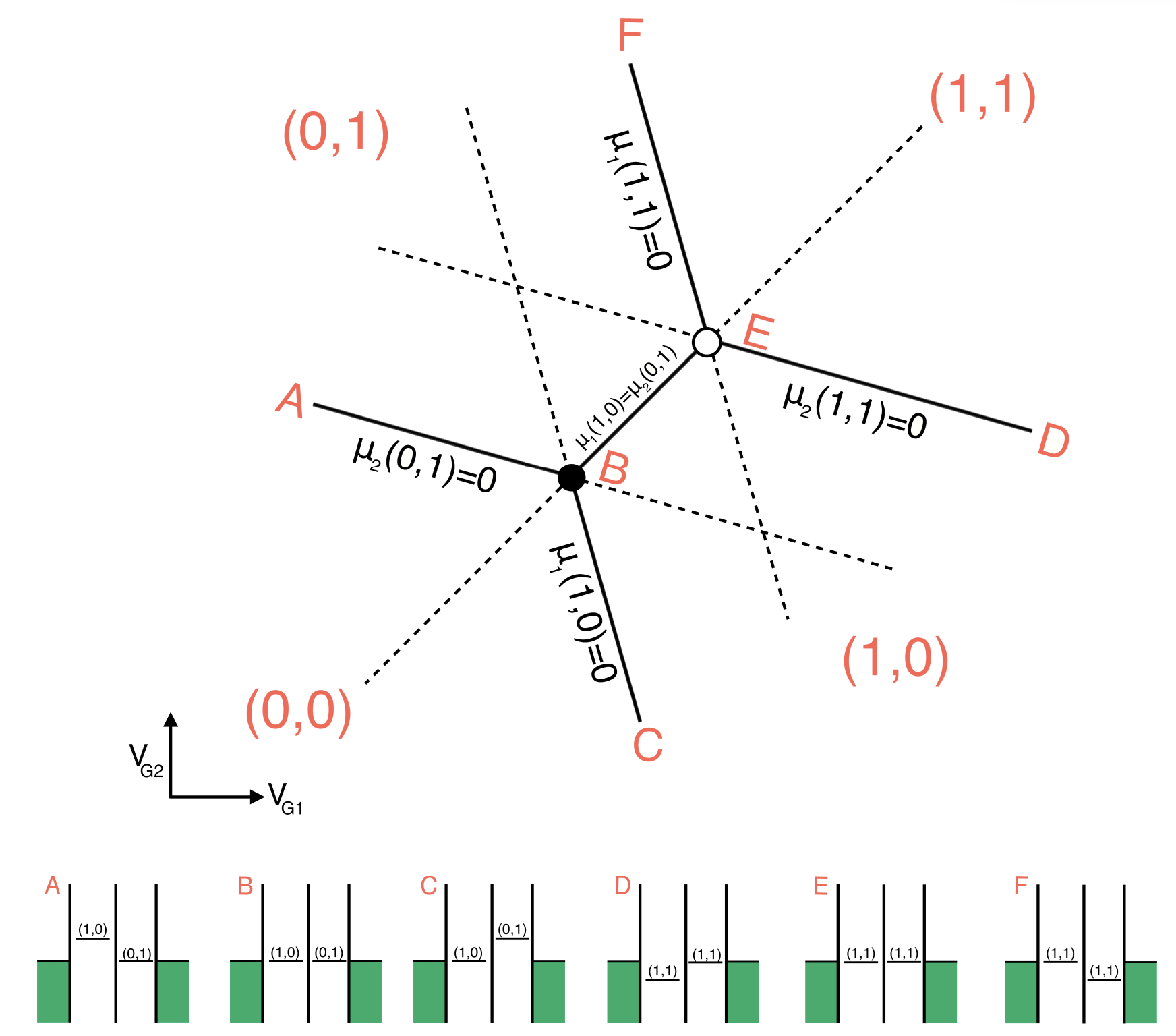

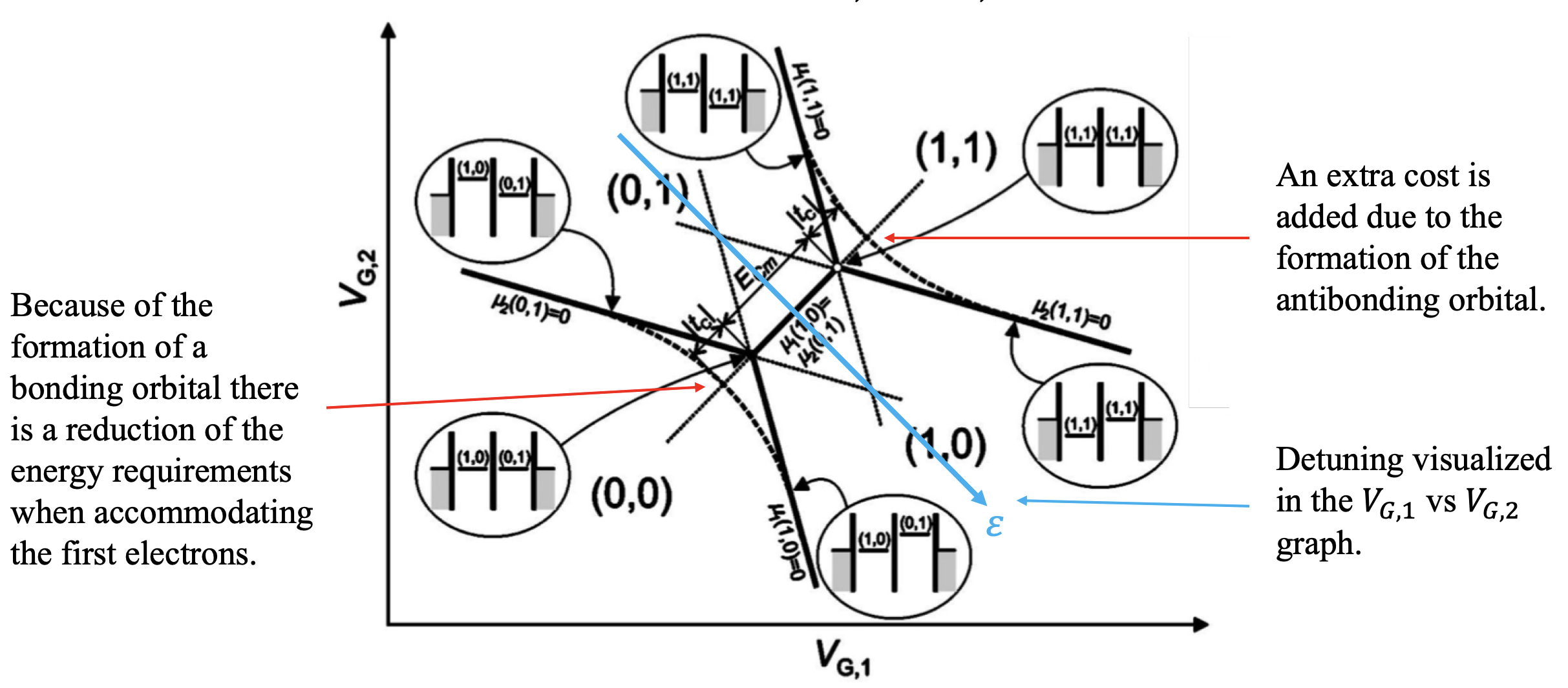

Stability diagrams for double quantum dot systems. Inside each domain the charge is constant, while on the edges of the border lines between the domains, charges can flow. The lines indicate the gate voltage values at which the number of charges changes. The number of charges on each domain is denoted by (N1,N2). These diagrams can be viewed as an extension in two dimensions of the coulomb peak diagram presented in figure

In A, the capacitive coupling between the two dots is negligible, making the two dots effectively independent.

For smaller distances, the electrostatic interactions between dots become significant

When the mutual capacitive coupling between the dots is greater than zero, it means that there is significant electrostatic interaction between the two quantum dots.

Triple Points: At certain gate voltages, the electrochemical potentials of the two quantum dots align with the source and drain, allowing electrons to tunnel onto and off the dots. These gate voltages correspond to the vertices of the honeycomb pattern and are called “triple points” because three different charge configurations are energetically degenerate. Only on these points, a current can flow from source to drain.

Focus on the triple points:

Tunneling coupling

When distances are small, tunneling between dots can occur. Much like superlattices, this leads to a change in the levels of the dots. In superlattices we had a periodic structure. Here, instead, we only have two dots. The configuration recalls the one of a molecule made of two atoms.

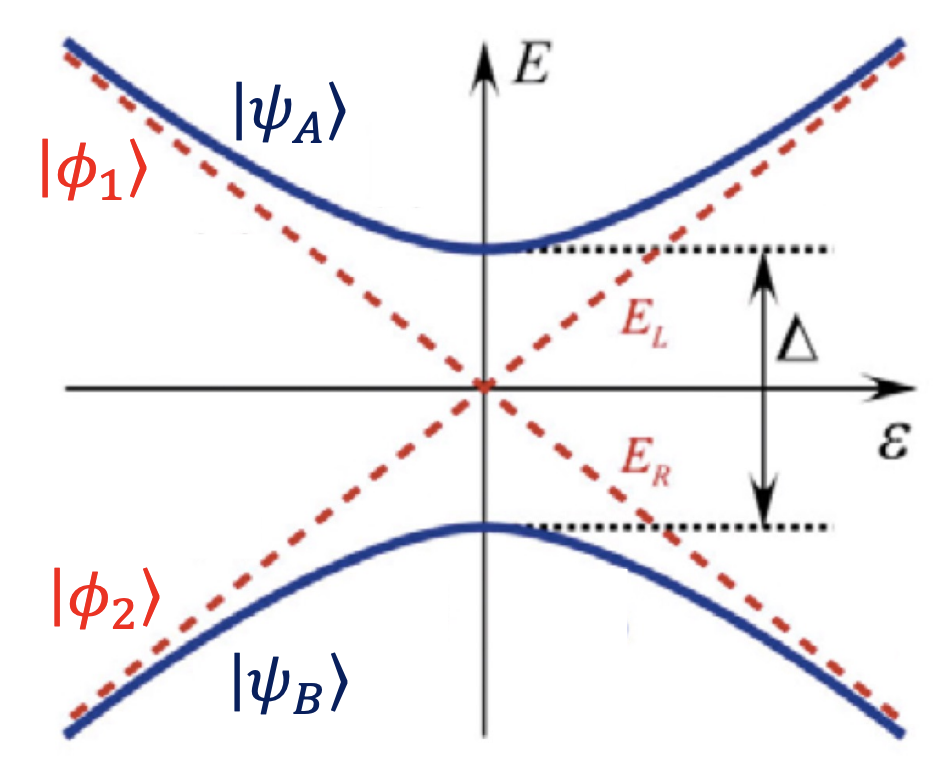

Therefore, because of the tunneling coupling (

-

Bonding Orbital

-

Antibonding Orbital

Detuning

Detuning (

For two coupled quantum dots, detuning is typically controlled by adjusting the gate voltages applied to the dots. These voltages shift the potential energy landscape of the electrons in the dots, thereby changing their energy levels. When the levels are aligned, electrons can tunnel freely between the dots.

Bonding Orbital Formation: When the first electrons enter the quantum dots, they occupy the bonding orbital, a lower energy state resulting from the constructive interference of the wave functions from both dots. This means it takes less energy to add an electron because they’re effectively sharing the space between the two dots, which is energetically favorable. This is shown as a reduction of energy requirements in the diagram.

Antibonding Orbital: are shown as an extra cost in the diagram.

Detuning: This is represented by the diagonal lines in the diagram and indicates the energy difference between the levels of the two dots. When the dots are detuned, one dot’s energy level is higher or lower than the other’s. By adjusting the gate voltages, one can control the detuning and thus control the electron tunneling between the dots.

Qubit

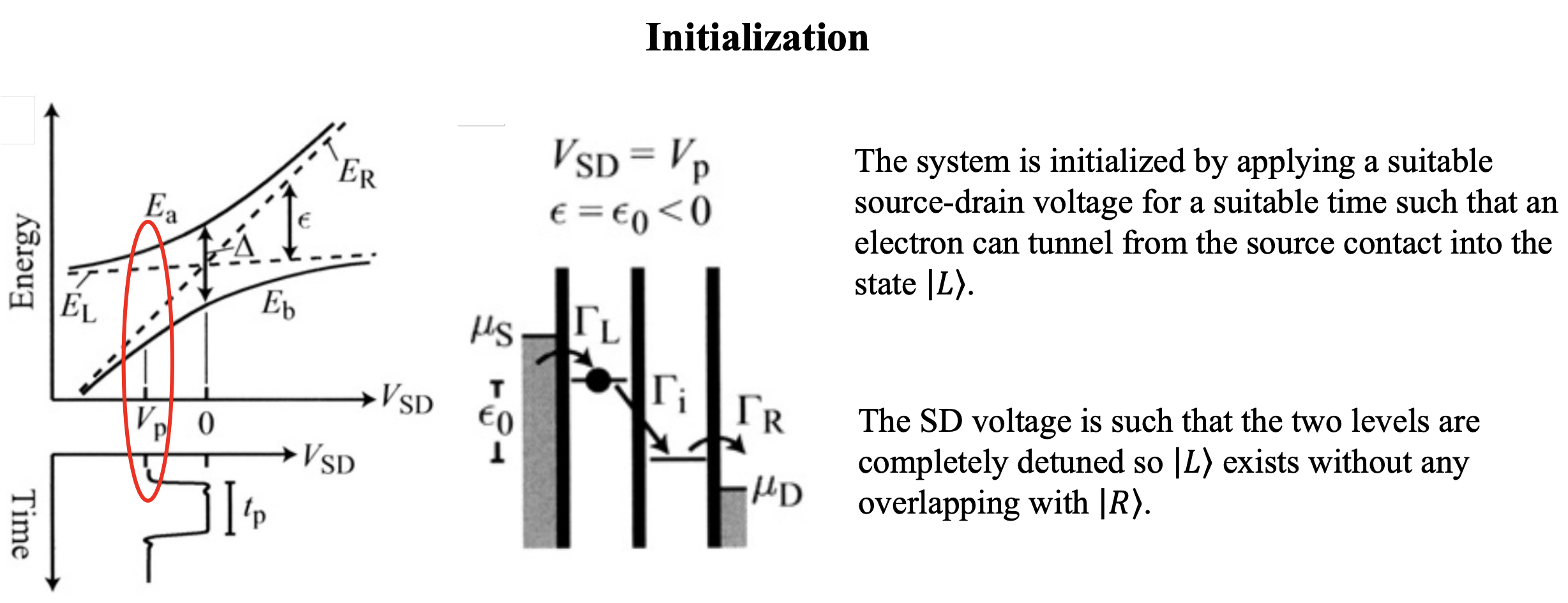

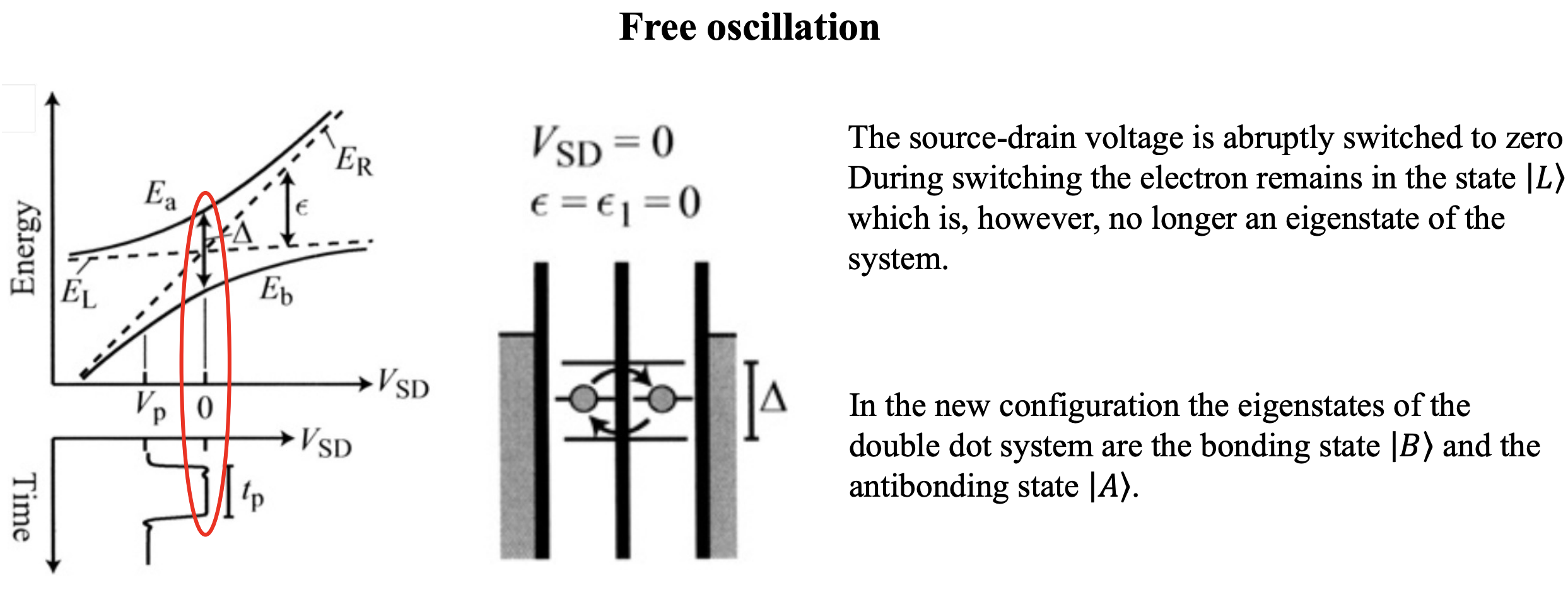

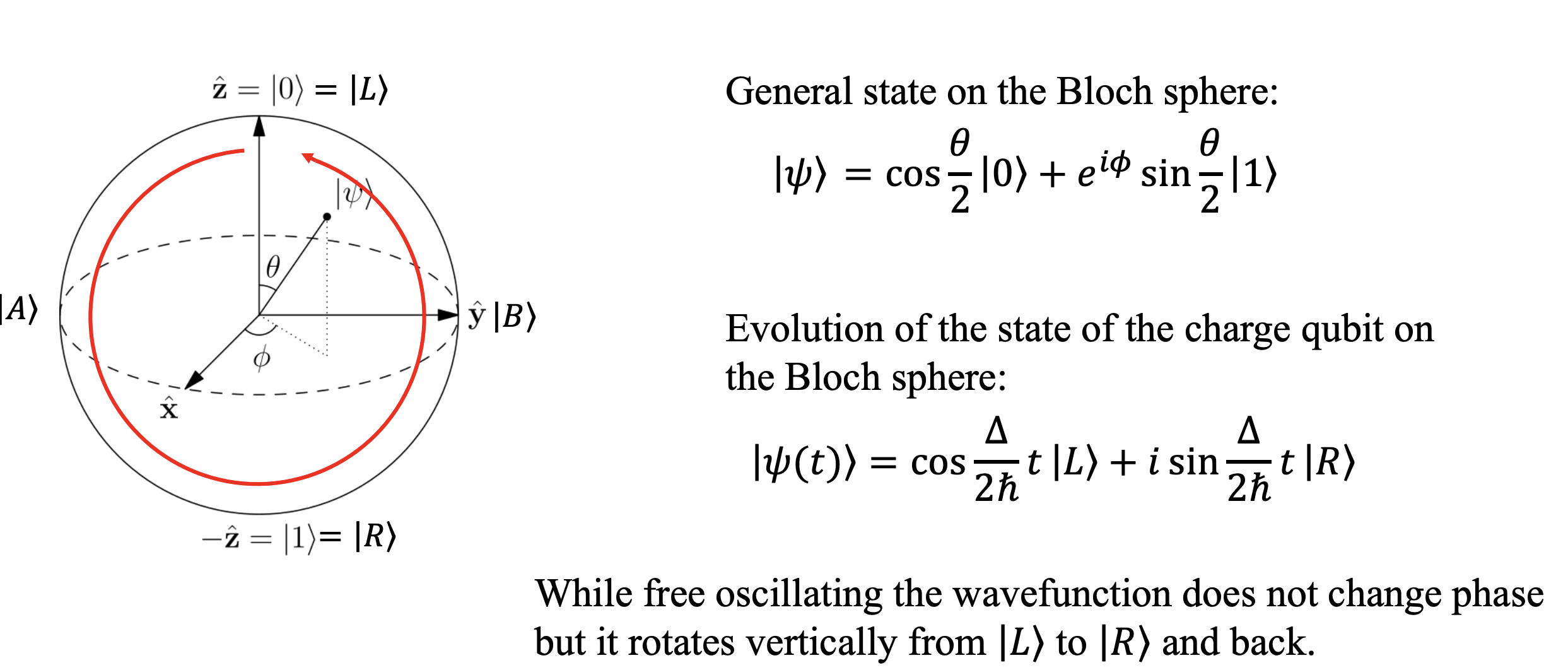

We can use a double quantum dot structure, for example, based on a heterostructure with a two-dimensional electron gas, to create a singlequbit. Depending on the voltage we apply, the dots states are either split (large detuning) or hybridized to form bonding and antibonding orbitals (small detuning).

The two basis states of the qubit are taken to be the two charge states

The bonding and antibonding states are superimpositions of the left and right states: