Qubit

A qubit is the fundamental unit of information in quantum computing. In contrast to classical bits, which can only exist in one of two states (0 or 1), qubits can simultaneously exist in multiple states thanks to the superposition principle in quantum mechanics. Qubits can be realized through diverse physical systems, including atoms, ions, or superconducting circuits.

We start creating a quantum system with only two states (or focusing only on this two states)

Since

We want to represent the qubit geometrically and to do this we need to decrease the number of parameters. Fortunately not all 4 values above are independent:

we have written the qubit using the polar coordinate system.

Now we can manipulate the qubit as following:

Since global phases do not have observable effects in quantum mechanics, we can omit it when considering measurements on other physical phenomena (if you are not comfortable with this try calculating the expected value of a generic operator

then we remember that

where

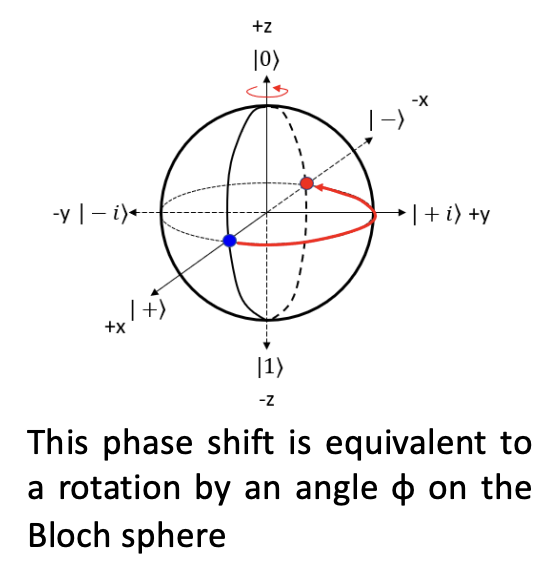

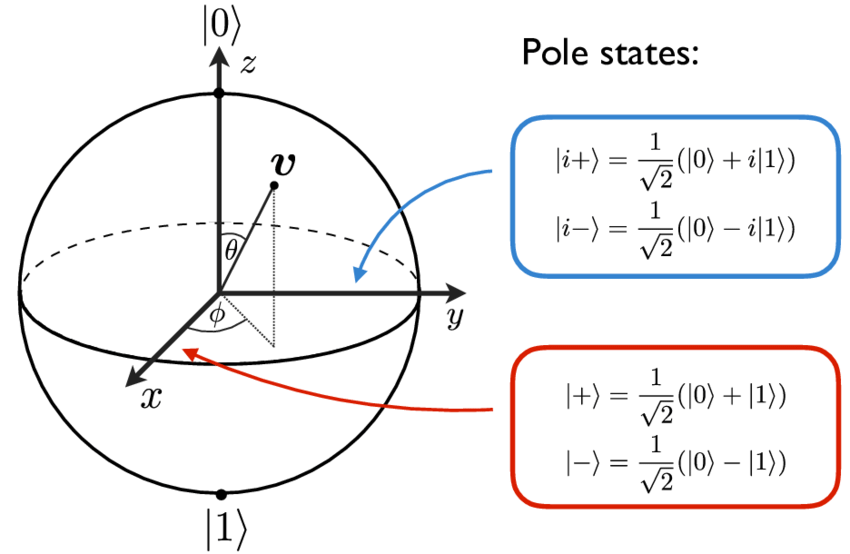

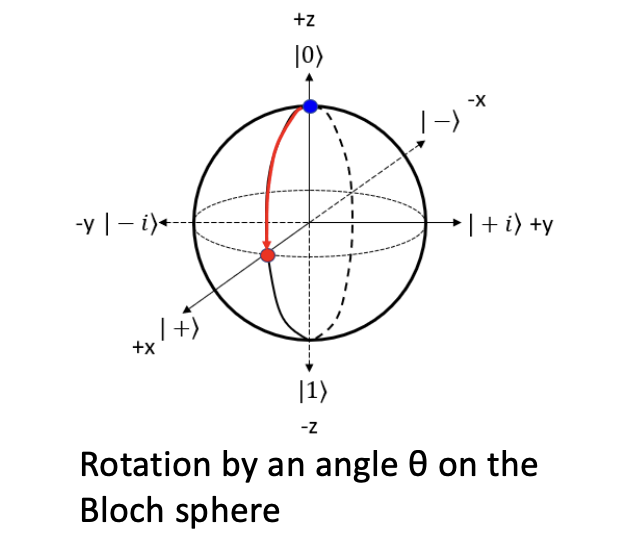

Bloch sphere

The Bloch sphere provides a clear geometric picture of the qubit state, making it easier to visualize and understand quantum operations. It captures both the amplitude and phase information of the qubit state.

- States along z-axis:

- States along x-axis:

To achieve experimentally the qubit we need to perform operations that allows us to address each point of the sphere.

Flying Electron Qubit

Flying qubits have a more restricted use case than stationary ones: they are only used to propagate the information between macroscopic distances, whereas stationary qubits are used to not only store information, but also to perform calculations.

Why not

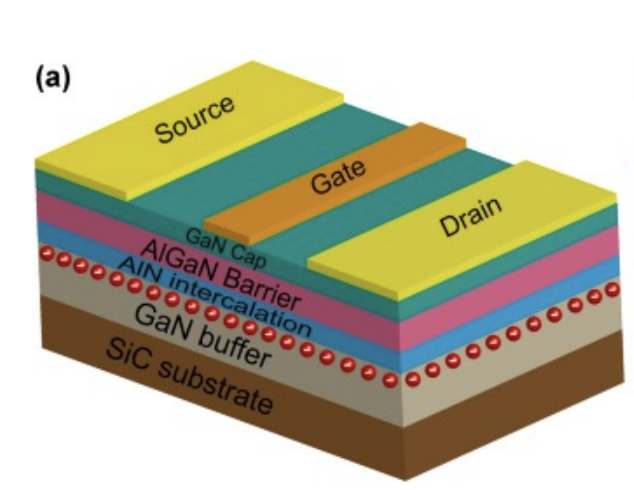

Flying electron qubits rely on electron waveguides, beam splitters and phase shifters. These fundamental building blocks of electron quantum optics are realised by high mobility, doped

Through the placement of metallic Schottky gates onto the

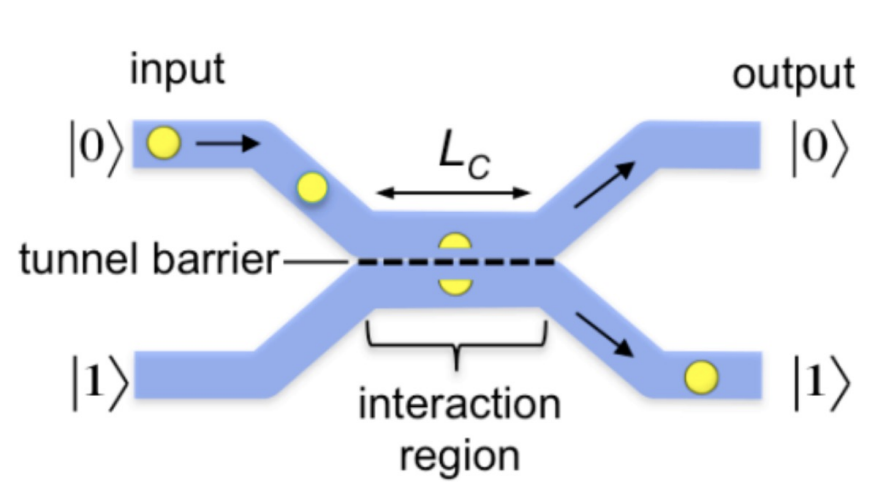

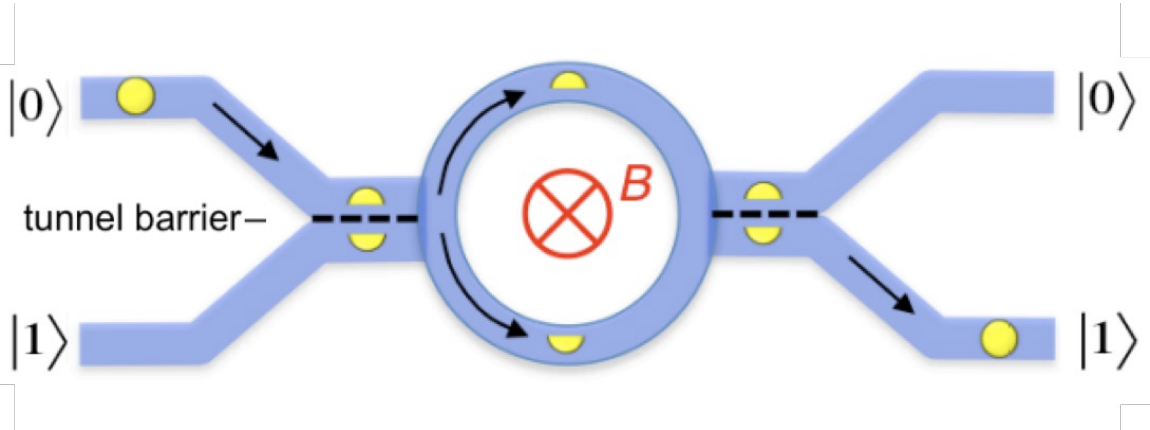

In its most basic form, a flying electron qubit is made of a propagating electron within two identical electronic waveguides. The qubit states,

-

Two Waveguides: The device consists of two identical electronic waveguides, which are paths that allow electrons to move. These waveguides represent the two possible states of the qubit:

and . The electron traveling in the upper waveguide represents the qubit being in state , and in the lower waveguide represents the qubit being in state . -

Tunnel Barrier: Between the two waveguides, there is a “tunnel barrier”. The height and width of this barrier can be adjusted to control the probability that the electron will tunnel from one waveguide to the other.

-

Gate Voltage: By applying a gate voltage, the height of the tunnel barrier is tuned. A higher barrier decreases the tunneling probability, and a lower barrier increases it. By fine-tuning this gate voltage, one can control the superposition state of the qubit.

The barrier allow us to control the

To completely control the state of an electronic flying qubit, we need to implement a rotation by an additional angle

Due to the Aharonov-Bohm effect, the phase shift introduced between the upper and lower path is proportional to the intensity of the magnetic field and the surface area enclosed by the two paths.