QWs SUPERLATTICES

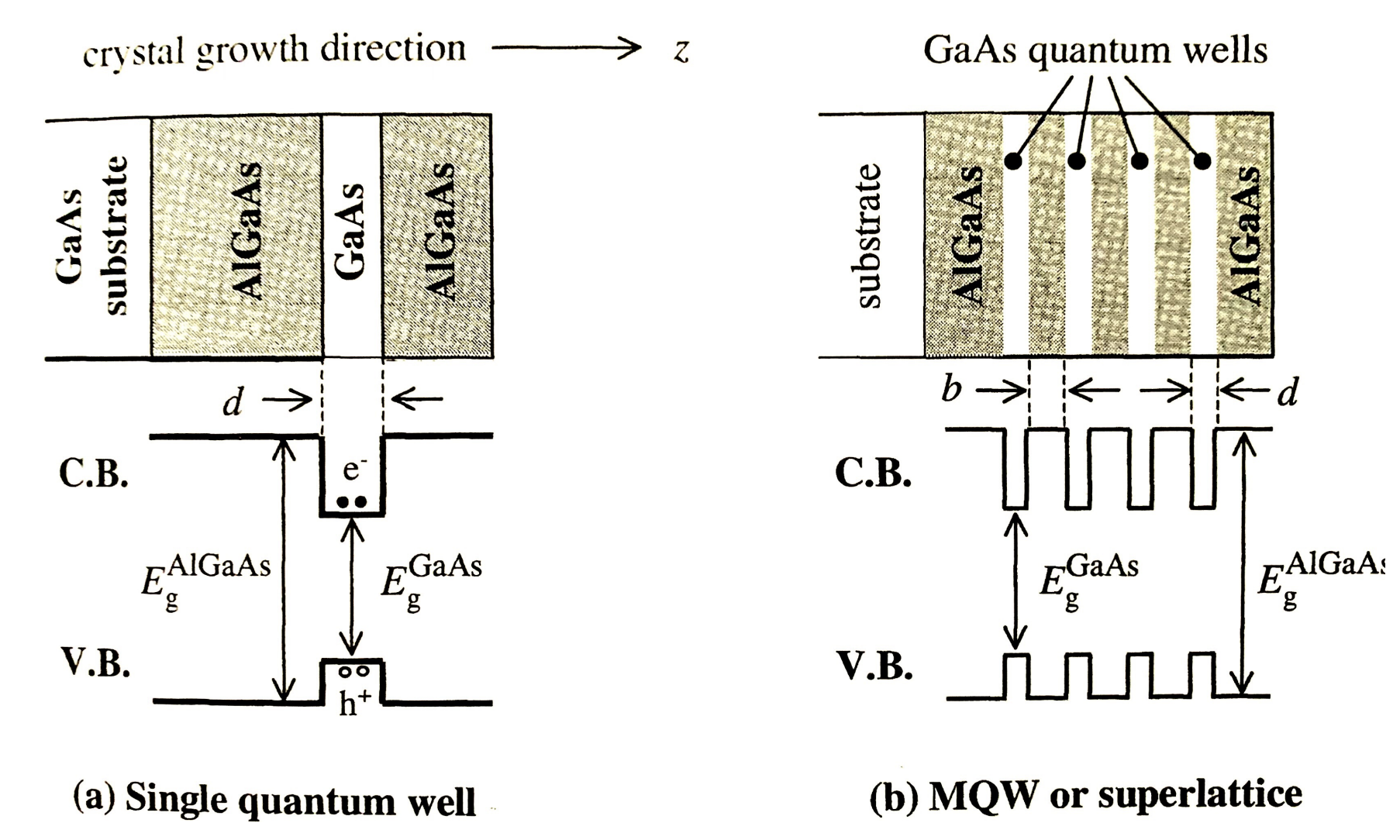

A QW superlattice is formed by stacking multiple quantum wells. The barrier layers are usually made of a material with a larger band gap than the quantum well material. The close proximity of multiple quantum wells allows for the wavefunctions of electrons in adjacent wells to overlap (if the barrier has the right width).

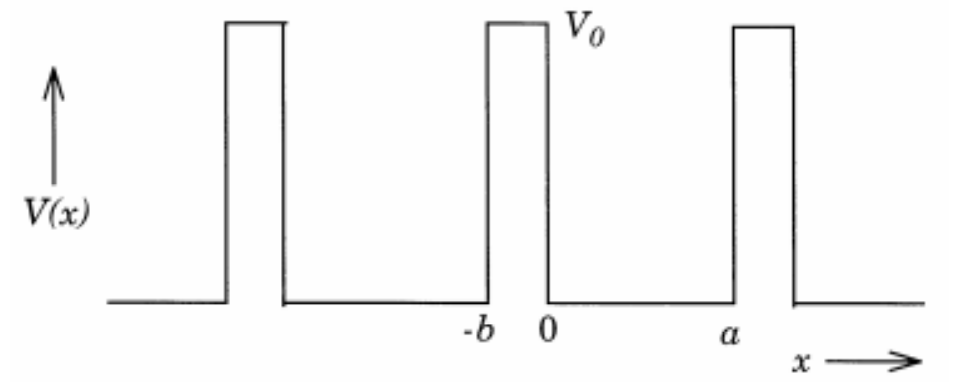

For the square potential well, we could apply the Kronig-Penney model to solve the Schrödinger equation.

The figure shows the periodic potential with period

so we can write the TISE for the two regions:

Then the solutions would be:

Since we are interested in the case in witch

Due to the periodicity of the structure we consider the following boundary condition and the Bloch theorem:

so for

substituting with the wave function:

also the derivative must be continuous:

substituting with the wave function:

now using the two equation from the boundary condition and the other two from the Bloch theorem we can solve the system of the 4 unknown (

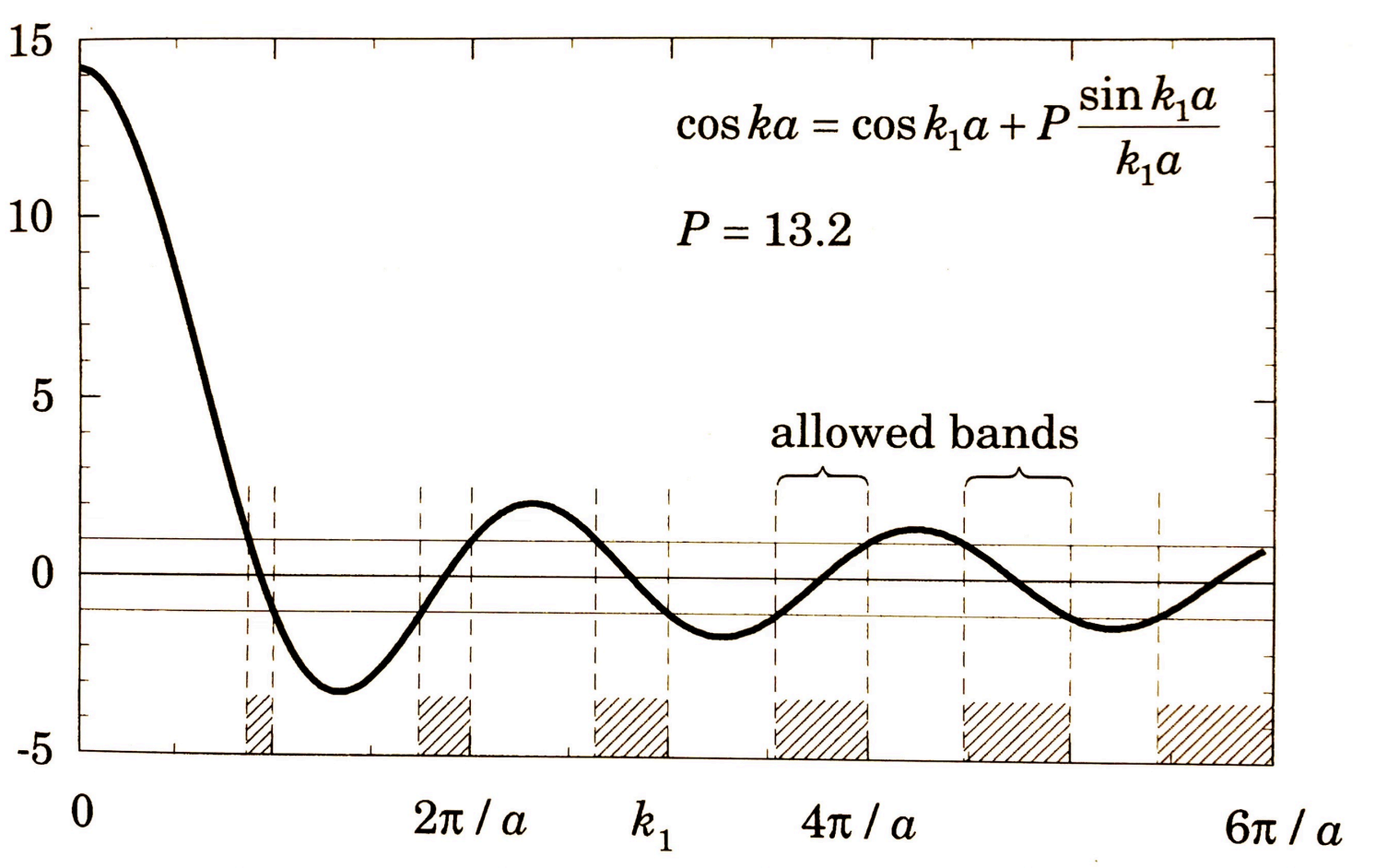

Plotting one side of the equation:

the only allowed region are thus for which the cosine lie between -1 and 1.

the only allowed region are thus for which the cosine lie between -1 and 1.

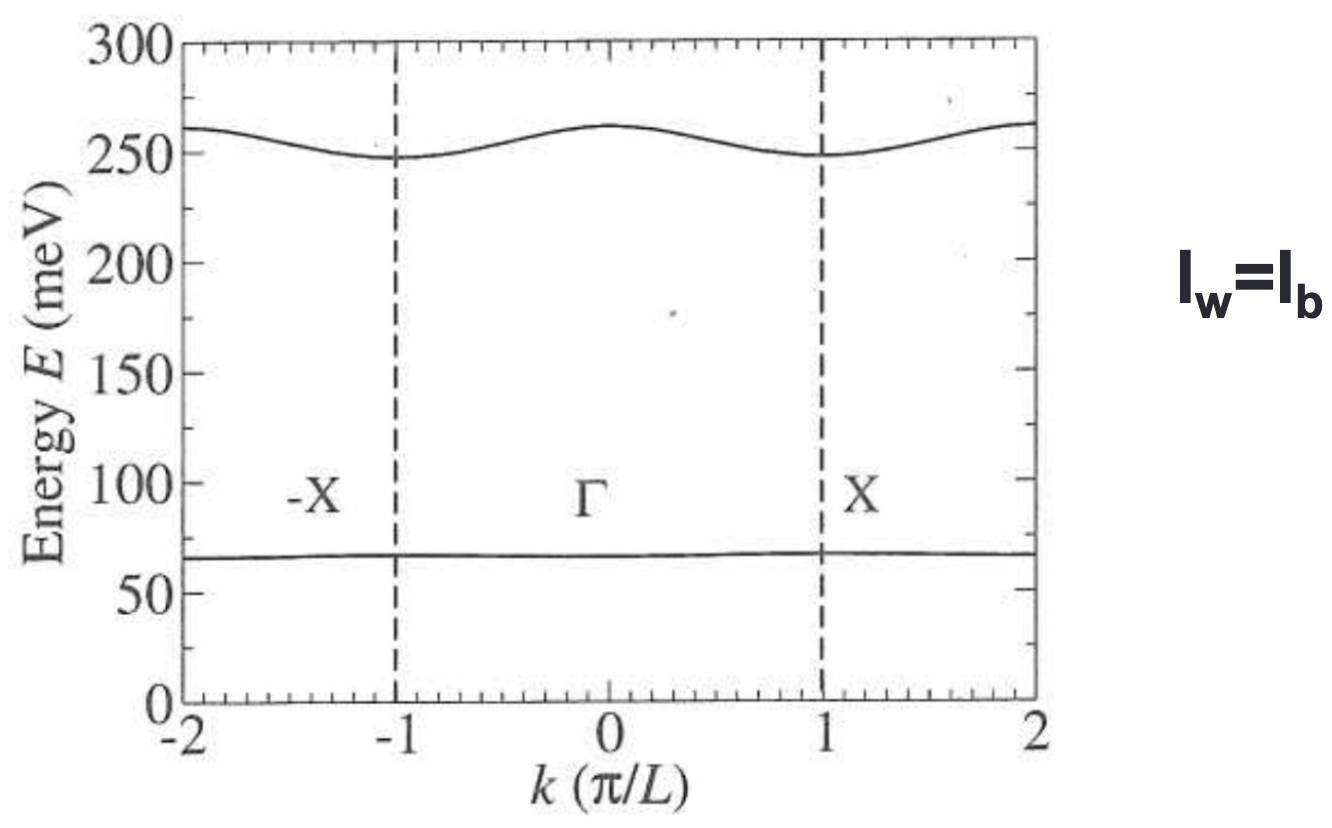

The domain in k-space has become known as the SUPERLATTICE Brillouin Zone. Just as a QW can have more that a confined state, superlattices can have more that a miniband:

the slope of the band is related to the velocity of the electron inside the superlattice, which is different from 0, contrary to the QW case where

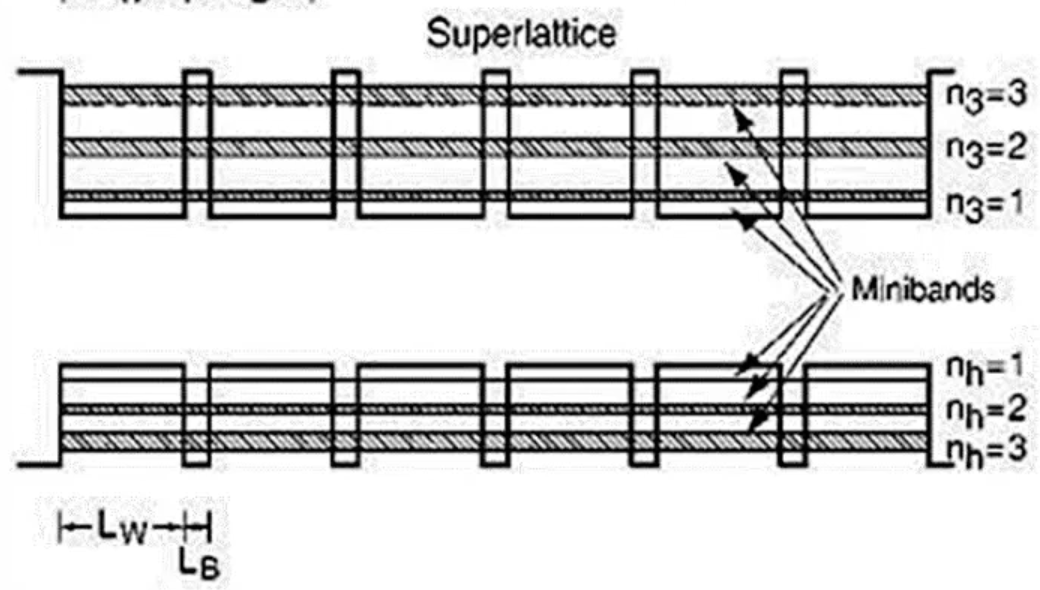

Schematic diagram of a Superlattice, showing the formation of minibands from the energy levels of the corresponding single QW. The structure forms an artificial one-dimensional crystal with period (

The width of the band change with

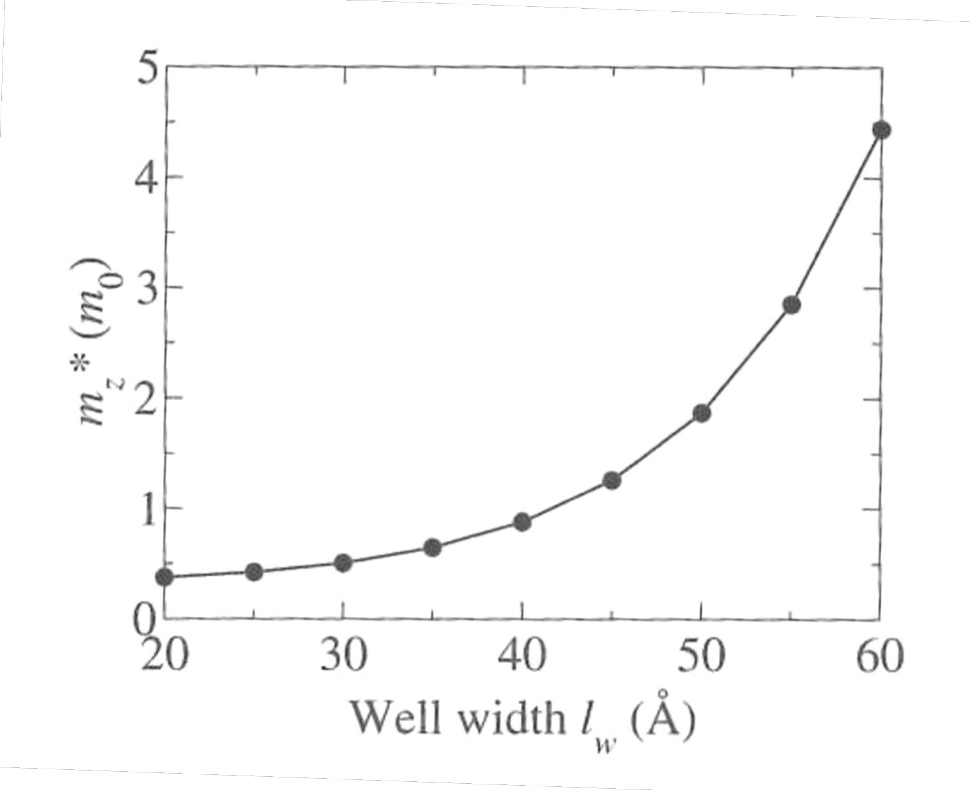

The graph shows new value of effective mass for an electron at

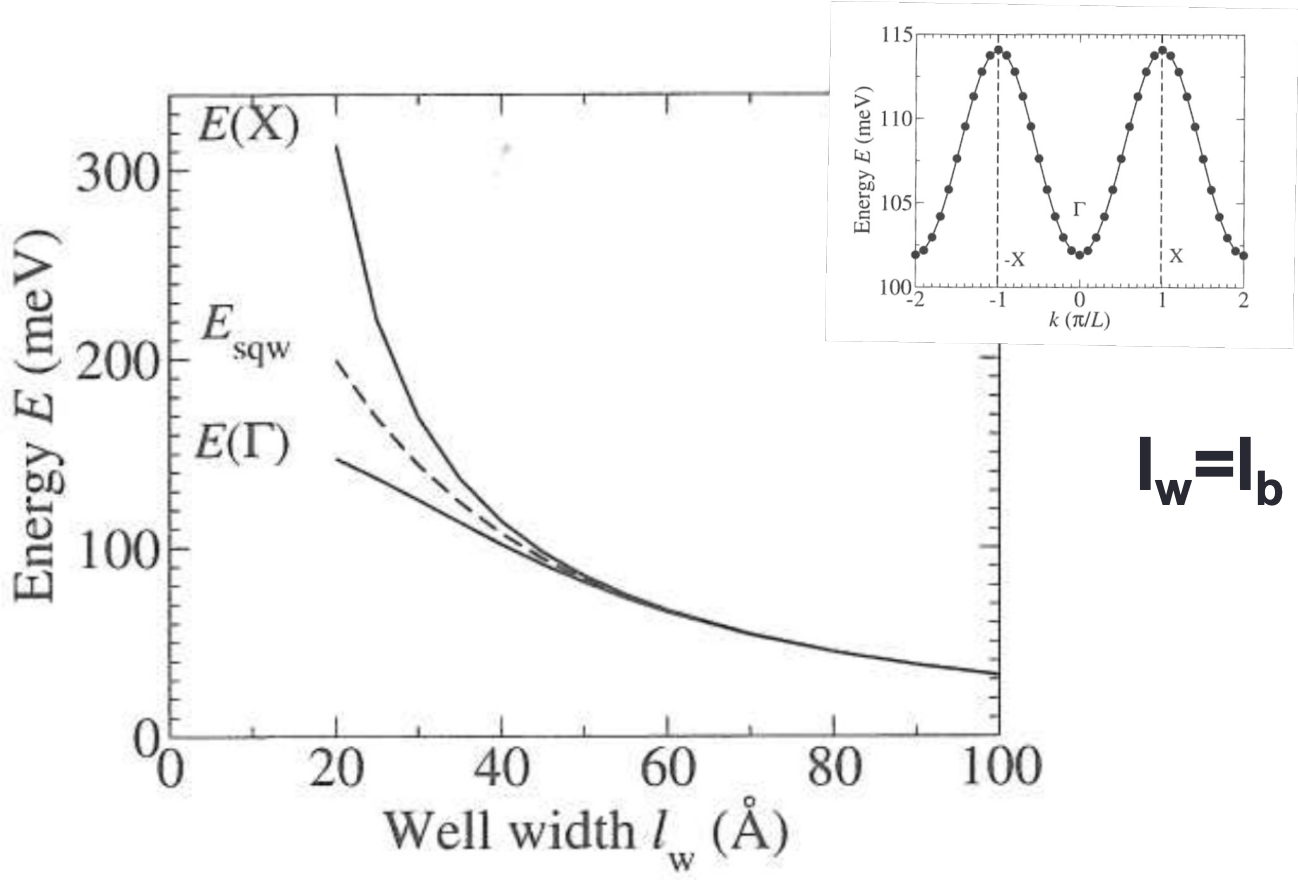

Energy comparison between superlattice and SQW

The graph presents the energy levels at

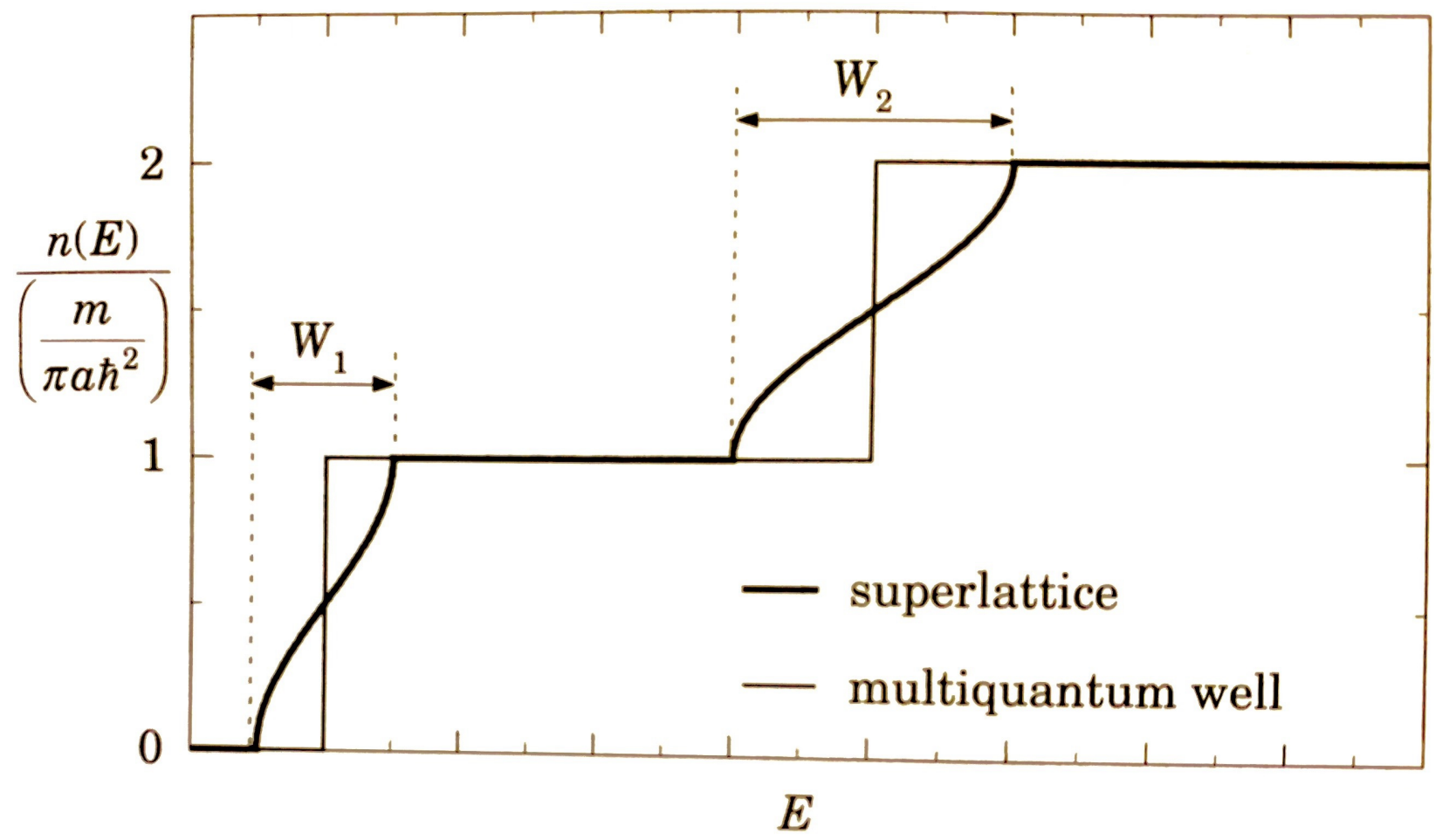

Density of states of the superlattice

The density of states (DOS) in a superlattice differs significantly from that of a 2D multiple quantum well (MQW) due to the presence of minibands. In the superlattice, the DOS transitions between levels are not abrupt but exhibit a parabolic shape, reflecting the gradual filling of these minibands. Notably, the shift in the DOS at the first miniband level is less pronounced compared to the second, which can be attributed to the smaller width of the first miniband in comparison to the subsequent one

QCL (Quantum Cascade Laser)

ISB

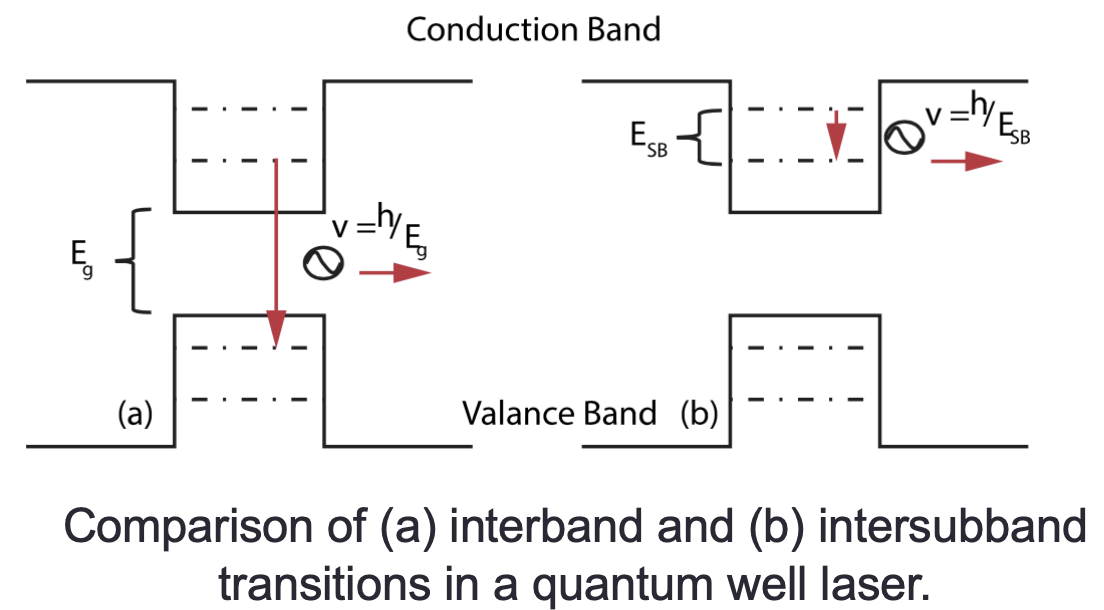

The engineered band structure of QWs leads to the possibility of inter-subband (ISB) transitions which take place between confined states within the conduction or valence bands. The transitions typically occur in the infrared spectral region. Intersubband emission in superlattices is at the base of the operating concepts of the Quantum Cascade Lasers (QCL).

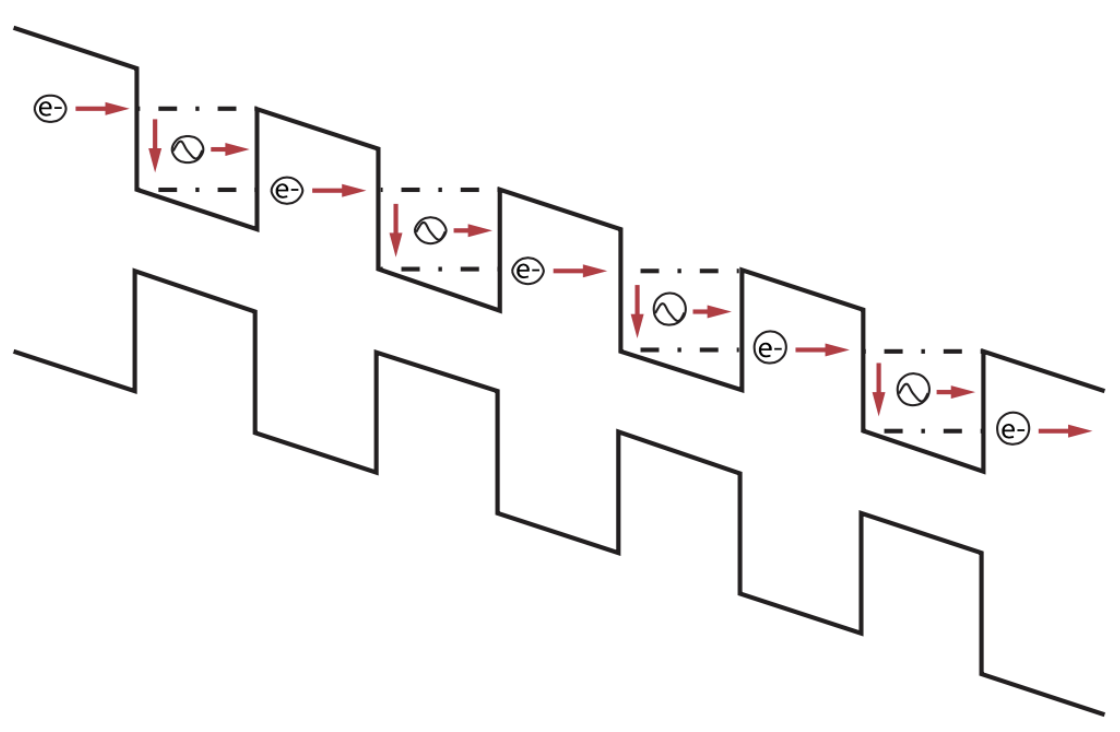

When combined with a sloped potential bias from well to well, a single electron can cascade through the quantum well structure and emit multiple photons, as shown in the figure above. As a result, QCLs can produce high power at long wavelengths through the combination of both quantum and cascade effects. Emission occurs in the IR region (application to IR emitters, IR sensors, gas sensors.

The QCL, which was first demonstrated in 1994 at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, NJ, is a semiconductor laser, but it operates under very different physical principles than traditional semiconductor diode lasers. Diode lasers achieve stimulated emission through electron-hole recombination between the conduction and valance band. In a QCL, one uses tens or even hundreds of quantum wells to decouple the emission wavelength from the bandgap energy entirely. The decoupling results from the formation of subbands in the conduction band, allowing for stimulated emission to occur within the conduction band itself, this is known as an inter-subband transition. Under these circumstances, stimulated emission does not result in electron-hole recombination, leaving the electron within the conduction band. The wavelength of the emitted light is determined by the energy differences between these subbands, not by the material’s bandgap. This allows for greater flexibility in designing the laser to emit at specific wavelengths.

Bloch oscillation

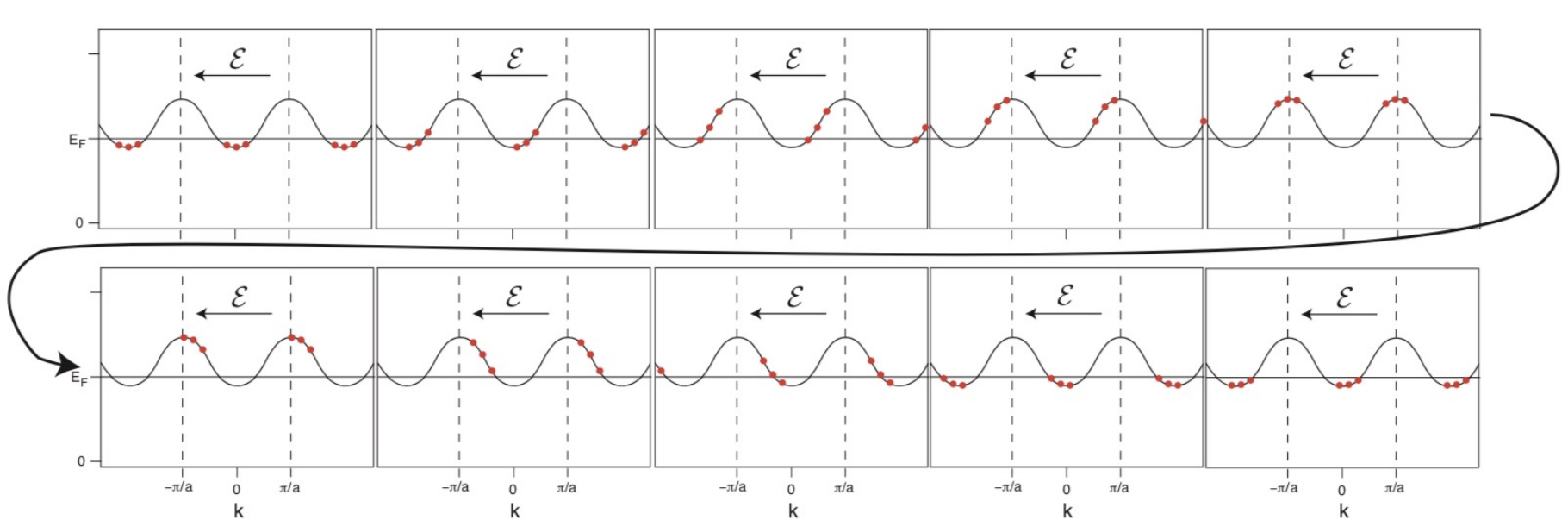

Is a phenomenon from solid state physics. It describes the oscillation of a particle (e.g. an electron) confined in a periodic potential when a constant force is acting on it. The motion of electrons in a perfect crystal under the action of a constant electric field would be oscillatory instead of uniform.

While in natural crystals this phenomenon is extremely hard to observe due to the scattering of electrons by lattice defects, it has been observed in semiconductor superlattices.